dom lizarraga

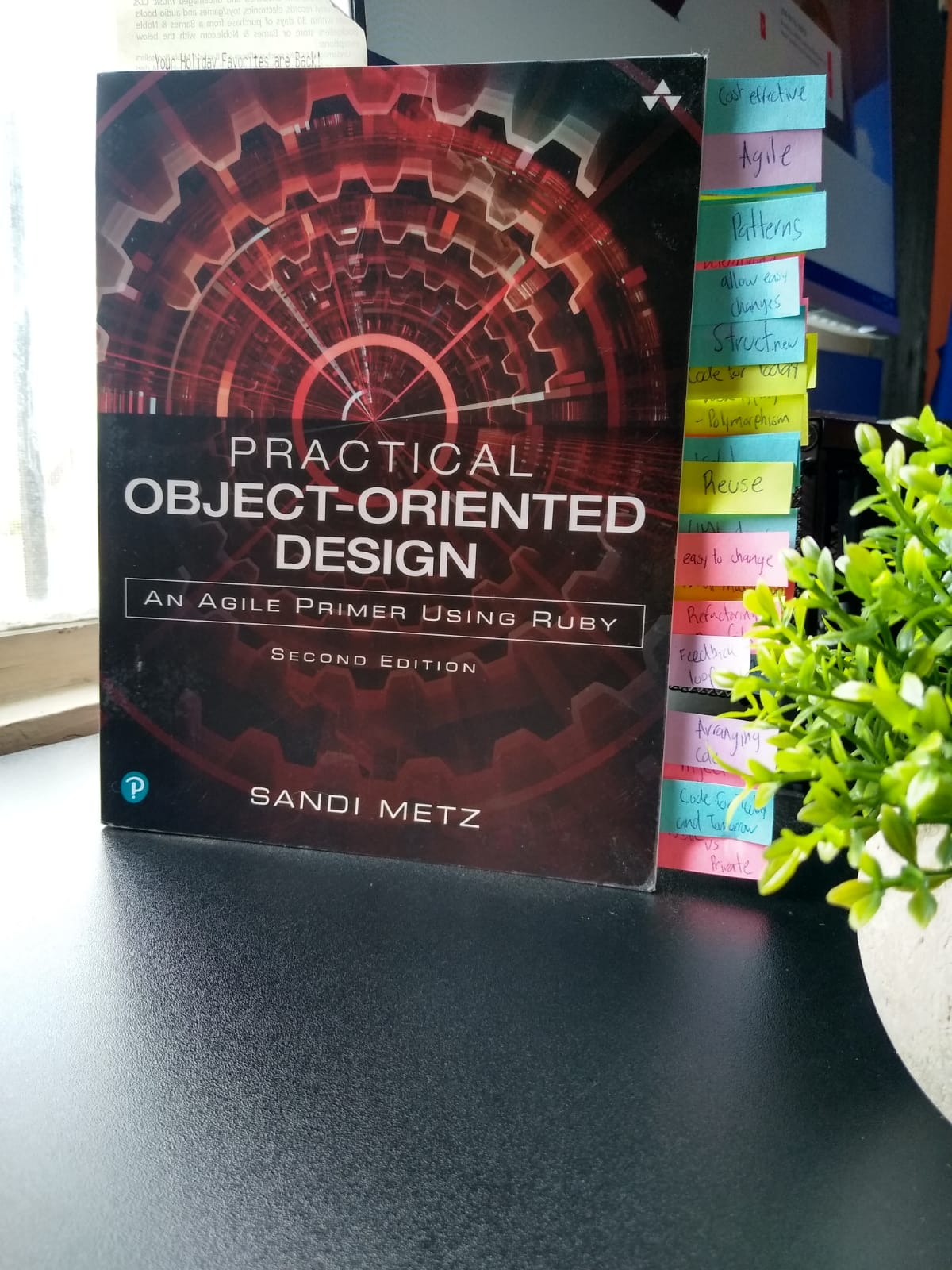

I read Practical Object-Oriented Design (POODR) by Sandi Metz on May 30, 2021

Review

This book is the second edition that Sandi Metz publishes and it’s even considered as a must-read by the RoR community, give it a shot you won’t regret at all no matter what language you’re coming from.

The introduction gives you why we want to work at a place where we feel as if we had some real impact, without being painful and why not make it funny as well, also explores the idea of increasing the productivity and reducing costs associated with poor design software.

It goes over some agile methodology; it brings up the “Agile Manifesto” and explores its points of intersection between project management and software development.

The core example of the book is a Bicycle store and it starts with the most simple but thorough class and it gradually increases its complexity always by giving you the reason why would you for instance need to add spare parts method to the main class or create a new one from scratch, what are the benefits and downsides? Is the customer really requesting this? What if we go beyond the scope of the app and make it flexible since the beginning? And finally, you end up with a Bicycle store and an app to book trips. 🚲 🏔

It offers many examples of all the good practices or rules you may find below and gives you the before and after of each scenario, and you can find the most important examples in my repository. https://github.com/DominicLizarraga/refactoring_ruby_edition

Chapter 1. “Object-Oriented Design”

Encourages you to shift your thinking from a world of collection of predefined procedures to modeling the world as a series of messages that pass between objects.

It depicts that statement with an example of a woman waking up at the same hour, preparing her coffee and suddenly steps on the cat, causing a reaction that was not on the normal routine. 🐈

It also elaborates on the idea that the only sure thing that will happen is that your app will need some changes, it’s impossible to never change. It includes some customer perspective and how the client doesn’t not even know what they want so you must be ready for progressive modifications.

“You must combine an overall understanding of your application’s requirements with knowledge of the costs and benefits of design alternatives and then devise an arrangement of code that is cost effective in the present and will continue to be so I the future.”

“The purpose of design is to allow you to design later, and its primary goal is to reduce the cost of change.”

The chapter 2. “Designing Classes with a single responsibility”

The foundation of an object-oriented system is the message, but the most visible organizational structure is the class.

Your goal is to model your application, using classes, such that it does what it is supposed to do right now and is also easy to change later. Creating an easy-to-change application, however, is a different matter. Your application needs to work right now just once; it must be easy to change forever.

The problem is not one of technical knowledge but of organization; you know how to write the code but not where to put it.

When it says easy to change it means the following:

• changes have no unexpected side effects,

• small changes in requirements require correspondingly small changes in code,

• existing code is easy to reuse, and

• the easiest way to make a change is to add code that in itself is easy to change.

A class should do the smallest possible useful thing; that is, it should have a single responsibility.

Chapter 3. “Managing Dependencies”

Because well-designed objects have a single responsibility, their very nature requires that they collaborate to accomplish complex tasks. This collaboration is powerful and perilous.

To collaborate, an object must know something know about others. Knowing creates a dependency. Ig not managed carefully; these dependencies will strangle your application.

Your design challenge is to manage dependencies so that each class has the fewest possible; a class should know just enough to do its job and not one thing more.

To some degree of dependency between these two classes is inevitable; after all, they must collaborate.

When two (or more) objects are so tightly coupled that they behave as a unit, it’s impossible to reuse just one.

Every dependency is like a little dot of glue that causes your class to stick to the things it touches. A few dots are necessary.

If prevented from achieving perfection, your goals should switch to improving the overall situation by leaving the code better than you found it.

If you get this right, your application will be pleasant to work on and easy to maintain. If you get it wrong, the dependencies will gradually take over and the application will become harder to change.

Depend on things that change less often than you do.

Injecting dependencies creates loosely coupled objects that can be reused in novel ways.

Isolating dependencies allows objects to quickly adapt to unexpected changes.

The key to managing dependencies is to control their direction.

Chapter 4. “Creating Flexible Interfaces”

It’s easy to think about object-oriented applications as being the sum of their classes, they are so very visible; and they spin around responsibilities and dependencies. There is design detail that must be captured at that level, but an object-oriented application is more than just classes. It is made up of classes but defined by messages. Classes control what’s in your source code repository; messages reflect the living, animated application.

Design therefore, must be concerned with the messages that pass between objects. It deals not only with what objects know (their responsibilities) but also with how they talk to one another. The conversation between objects takes place using their interfaces; this chapter explores creating flexible interfaces that allow applications to grow and to change.

Imagine two running applications. Each consists of objects and the messages that pass between them.

In the first application, the messages have no apparent pattern. Every object may send any message to any other object. If the message left visible trails, there trails would eventually draw a woven mat, with each object connected to every other.

In the second application, the messages have a clearly defined pattern. Here the object communicates in specific and well-defined ways. If these messages left a trail, the trails would accumulate to create a set of islands with occasional bridges between them.

The second application is composed of a pluggable, component-like objects. Each reveals as little about itself, and knows as little about others, as possible.

The design goal, as always, is to retain maximum future flexibility while writing only enough code to meet today’s requirements. Drawing this sequence diagram exposes the message passing between the objects.

The best possible situation is for an object to be completely independent of its context. An object that could collaborate with others without knowing who they are or what they do could be reused in novel and unanticipated ways.

Your goal is to write code that works today, that can easily be reused, and that can be adapted for unexpected use in the future.

Object-oriented applications are defined by the messages that pass between objects. This message passing takes place along “public” interfaces; well-defined public interfaces consists of stable method that expose the responsibilities of their underlying classes and provide maximal benefit at minimal cost.

Chapter 5. “Reducing Costs with Duck Typing”

The purpose of object-oriented design is to reduce the cost of change. Duck typed objects are chameleons that are defined more by their behavior than by their class.

Avoid getting sidetracked by your knowledge of what each argument class already does; think instead about what the object needs.

Concrete code is easy to understand but costly to extend. Abstract code may initially seem more obscure, but once understood is far easier to change.

Recognizing hidden ducks.

Case statements that switch on class

Uses of method: kind_of? and is_a?

responds_to?

Polymorphism in OOP refers to the ability of many different objects to respond to the same message.

Duck typing reveals virtual underlying abstractions that might otherwise be invisible. Depending on these abstractions reduces risks and increases flexibility, making your application cheaper to maintain and easier to change.

Chapter 6. “Acquiring Behavior through Inheritance”

This chapters offers a detailed example of how to write code that properly uses inheritance.

The idea of inheritance may seem complicated, but as with all complexity, there’s a simplifying abstraction. Inheritance is, at its core, a mechanism for automatic message delegation, if and object cannot respond to a received message, it delegates that message to another. A superclass can have many subclasses, but each subclass is permitted have one superclass.

Creating hierarchy has costs; the best way to minimize these costs is to maximize your chance of getting the abstraction right before allowing subclasses to depend on it.

The best way to create an abstract superclass Is by pushing code up from concrete subclasses.

Chapter 7. “sharing Role Behavior with Modules”

To reap benefits from using inheritance you must understand not only how to write inheritable code but also when it makes sense to do so. Use of inheritance is always optional; every problem that it solves can be solved another way. Because no design technique is free, creating the most cost-effective application requires making informed tradeoffs between the relative costs and likely benefits alternatives.

When formerly unrelated objects begin to play a common role, they enter into a relationship with the objects for whom they play the role.

Many object-oriented languages provide a way to define a named group of methods that are independent of class and can be mixed in to any object. In ruby these mix-ins are called modules.

When objects that play a common role need to share behavior, they do so via a Ruby module.

When a class includes a module, the methods in that module get put into the same look path as methods acquired via inheritance.

Chapter 8. “Combining Objects with Composition”

Composition is the act of combining distinct parts into a complex whole such that the whole becomes more than the sum of its parts. Music for example, is composed.

You can create software this same way, by using object-oriented composition to combine simple, independent objects into larger, more complex wholes.

A bicycle has parts. Bicycle is the containing object, the parts are contained within a bicycle. The Bicycle class is responsible for responding to the spares message. This spares message should return a list of spare parts.

The more parts an object has, the more likely it is that it should be modeled with composition.

Composition, classical inheritance and behavior sharing via modules are competing techniques for arranging code. Each has different costs and benefits; these differences predispose them to be better at solving slightly different problems.

Chapter 9. “Designing Cost-Effective Tests”

Without tests, these applications can be neither understood nor safely changed. They add value without increasing costs.

These are notes I took from the book, nothing is mine.

Details

- Practical Object-Oriented Design (POODR) by Sandi Metz

- Published: 2018