dom lizarraga

I read Professional Rails Testing by Jason Swett. on February 5, 2025

Review

This book has two parts, the first one goes over principles of testing, the second is about the tools you can use to test your code base.

- Chapter 1. Introduction.

- Chapter 2. Tests as specifications.

- Chapter 3. Test driven development.

- Chapter 4. Writing meaningful tests.

- Chapter 5. Writing understandable tests.

- Chapter 6. Duplication in test code.

- Chapter 7. Mocks and stubs.

- Chapter 8. Flaky tests.

- Chapter 9. Testing sins and crimes.

- Chapter 10. Ruby DSL.

- Chapter 11. Factory bot.

- Chapter 12. RSpec syntax.

- Chapter 13. Capybara’s DSL.

Chapter 1. Introduction.

The first chapter is about what you can expect from the book, why the author chose Rspec over Minitest and the ways you can reach out to Jason Swett.

Chapter 2. Tests as specifications.

The 2nd chapter aims to lay out what a test is, in this case the author rejects the idea that tests are verifications, rather they are specifications and with this definition the objective of testing goes from “make sure the code worked” to “enforce the code behave as specified”.

He also provides an example of a manufacturing site where all of its finished products behave the same way because they meet their design specifications due to its production system therefore it produces that same throughput always.

He also shares that the main challenge is to switch developer’s mindset from verification to a specification, this will entail moving from “capabilities” to “scenarios”.

the next examples are going to be capabilities:

the user can update their email address the user can sign in the user can reset their password

on the other hand we have scenarios, for instance: when the user signs in with a valid credentials, the dashboard page will show up when the user attempts to sign in with invalid credentials and error message is shown

A specification is a statement of how some aspect of a software product should behave. Again departing from the scenario point of view and we can break it down to the following:

Scenario: when a user enters a valid email and password combination into the email and password fields, then clicks ‘sign in’

Expectation: the user dashboards page is shown.

This is a style that the author has conceived and he denotes that it makes sense to him but it is not a golden rule, in other words “under such-and-such a scenario, we expect such-and-such behavior”

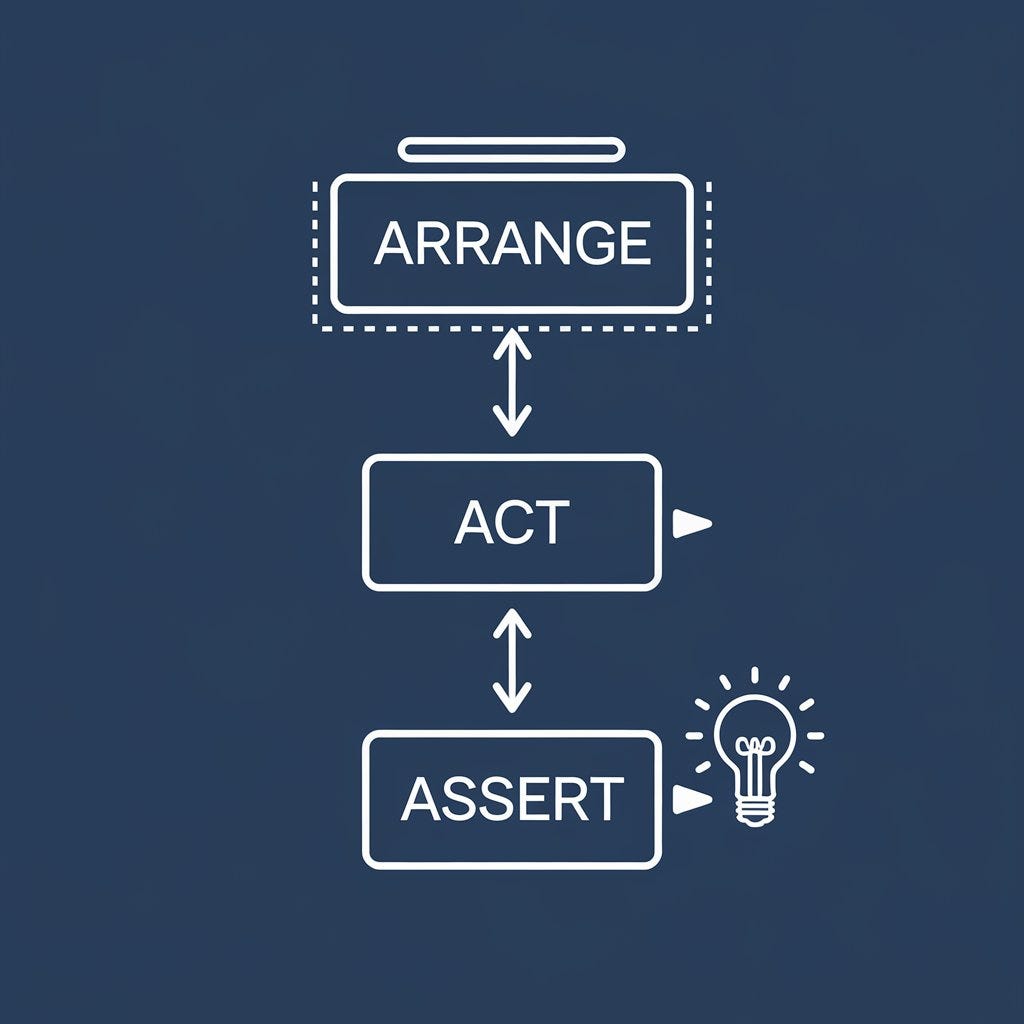

The author describes with an example of a parser program the same pattern of a scenario and expectation and it goes step by step from creating the file, adding some boilerplate, starting with some comments in order to remove the writer’s block and finally he quotes the ‘arrange act and assert’ phases.

Small recap: Scenario (what to test, we can remember this with words like “when” or “given”) Expectation (We can remember with the keyword “then”) Setup, exercise and assertion ( arrange act and assert)

Source: Medium

Chapter 3. Test driven development.

Chapter 3 is about TTD (test driven development) he briefly describes what it is, pointing out why it is often called the ‘red, green, refactor loop’, what do those colors mean? and finally the importance of refactoring the code you wrote.

Red: Firstly we start with deciding “what to do” and then “doing it” (this reduces cognitive load) keeping in mind that a test is an executable and “specification”. We first write the test so we set out the ‘specification’ and then we write the code to fulfill given a specification. Something important here is to run the test so we can clear out any false positives on the code, by running it and getting the red color we make sure that it is failing.

Importance of the green color and as the author quotes ‘Kent Beck’ you can make any ‘sins code’ in order to make the code pass, this means to write crappy code but make sure that you pass from red color to green color.

Also the author describes that if the whole system is covered by testing, we can refactor the system code as much as we want without too much fear that refactoring will introduce regressions. It is not an absolute warranty but it provides high degree of well justified confidence.

The author also said that he focuses on writing just enough code to make the current failure message go away, maybe not passing the whole test but just a small bit of it.

And finally ‘refactor’ this is where all the mess is cleaned up, duplication is removed maybe some optimization is added and here the author again shares one of his personal exercises that once he have passed the testing he hold off and give himself sometime to forget about the problem because it is very embedded in his brain and the refactor is not going to be very effective, instead he takes some time and then comes back and address the exact pain

Here is one statement about TDD that I liked “ the main reason for practicing TDD is to go faster and be more productive in simpler terms you want to decrease the radio of effort invested to Value produced”

TTD also encourages modular, loosely coupled design, less mental effort, more enjoyable workflow, fewer bugs, documentation, feedback loops (most important I personally think!)

Here is the feedback loop that TDD can create: specify an objective devise a test that can be performed to see if #1 is done perform the test device in step 2 do some work toward the objective ( wright a line of code) repeat steps three and four until the test passes repeat from step one with a new objective

Some notes from the author that I think are worth is when you write a line of code it is going to help us the message failure to go away so we can avoid coding speculatively and this will help us lower the mental burden in each step of this feedback loop,

Lastly the author closes this chapter by comparing the ‘manual testing‘ versus the TDD that as much as you practice it, you’ll get more fluent and it will become a great time saver

Chapter 4. Writing meaningful tests.

The author states that having tests is better than not having tests but not always writing tests are equally good tests are more valuable when they are meaningful.

A test is Meaningful if it tests not just means to ends but ends themselves.

When we are testing something we can focus either on means or ends, for example if we test a staple by just examining if it has all the right parts and just trying to staple 3 sheets of paper. By making sure that it has all the right parts it doesn’t mean we are testing the ends. On the contrary, if we staple 3, then 12, 20 and we can affirm that we can continually do this activity, that’s when we test the ends.

When it comes to testing model associations it would be more meaningful to make assertions on the behaviors that these associations enable.

Another great example is that airplanes engines can be tested even without attaching the engines to an airplane.

How to decide what kind of test drive, here we only have cost and benefits, we want to achieve satisfactory test coverage while incurring the smallest cost possible.

System tests are the only type of test that proves that all the parts of your system are successfully working together without system tests. We could theoretically have a web application with a fully passing suite of unit tests even if the application is unable to successfully serve a single request.

Something that I have seen has always been trivial is % of test coverage and the author suggests the following:

What if we use a minimum number of system tests, perhaps one for the happy path and one or two more for the failure cases and then use fast unit tests for all the edge cases? This way we will get a reasonable level of confidence that our system works as a whole.

Then we have: how to test models (POROs), requests, background jobs, mailer specs, helper specs, view specs and view components.

Also we have a very important question “when to write a test and went to not”, remember that testing is not about right or wrong but about cost and benefits here are five questions:

- Is the behavior likely to ever break?

- If the behavior were to fail, would it fail silently?

- if the behavior were to fail, would it fail frequently?

- if the behavior were to fail, would the consequence be severe?

- Is the test easy to write?

If any of the answers to these questions is a yes, I write the test. If and only if all of the answers are negative I do skip the test.

The aggregate benefit of tests. It is common to want to get some sort of 80/20 benefit by only covering the most important 20% of the codebase tests. I think this way of thinking focuses on the benefit of individual tests while missing the aggregate benefit of tests. Remember cost and benefits of testing can be refactoring with no fear, gaining speed for development without even thinking Dusty’s part of the code base is tested well enough?

In a model do we need to test every method, again remember that we covered every Behavior not every method.

Chapter 5. Writing understandable tests.

I think this is the longest chapter but is the one that has more meat because it touches topics as code quality in tests, in this case “abstraction”, (we always hear about quality code of the app itself but not in tests), it revisits the what the ‘when’, the ‘given’, ‘then’ as a structure for the test. Also how to accommodate the different files you need in the rails app, when to use helper when those are helpful, what about concerns, when is a good practice to create a model without inheriting from ActiveRecord, how to preserve ‘cohesion’, also Rspec feature which is ‘shared examples’, what may cause obfuscation in the tests, whether you use ‘subject’ or ‘let’ in our specs, plus the author gives a very useful opinion about code duplication (he shares that duplication is okay when it comes to testing).

Something that I truly liked is when the author brings up that a codebase is like a story book so each file has to be seen as a chapter, where you see essential points and it remains on those essentials topics and also incidental/distracting things that may go on the footnote or appendix.

Tests are more than just a safety net to catch regressions. A test suite can serve as a guidebook to a system, showing what the system’s parts are, how the parts relate to each other, which ideas are more and less important, and of course, how are the parts of the system are supposed to behave

A test suite is a structured collection of behavior specifications, and can also serve as the backbone for a systems design.

It is common to think of a system’s code as its essence and the tests as something secondary. I invite you to think of it the other way around. A system’s code shows what the system does, but the system’s application code does not have the last word. Because an application tests are specifications, whatever the test specifies is, by definition, correct.

So far we have mostly focused on writing new tests and writing them. but in a production application, in addition to being written and run, tests often need to be understood and modified.

Abstraction is the art of hiding distracting details and emphasizing essential information.

Test code is responsible for jobs that vary widely in the relevance to the high level meaning of the test. 1 test data has to be created. 2 dependencies have to be initialized. 3 code has to be finagled into the right state. 4 assertions have to be made, etc.

Here is a testing code example:

Before:

RSpec.describe "Creating Comment", type: :feature, js: true do

let(:user) { create(:user) }

let(:raw_comment) { Faker::Lorem.paragraph }

let(:article) do

create(:article, user_id: user.id, show_comments: true)

end

before { sign_in user }

it "User replies to a comment" do

create(:comment, commentable_id: article.id, user_id: user.id)

visit article.path.to_s

find(".toggle-reply-form").click

find(

:xpath,

“//div[@class=’actions’]/form[@class=’new_comment’]/textarea”).set(raw_comment)

find(

:xpath,

“//div[contains(@class, ’reply-actions’)]/input[@name=’commit’]).click

expect(page).to have_text(raw_comment)

end

end

The “it” block should describe how it (the system) should behave. To me the way this test description is written is a sign that this test is not the result of a clearly thought out specification

The next step is to think about the one or the given, in this case when user submits a reply to a comment or not article ( a scenario) the body of the reply shows up on the article’s page ( expectation)

After (with better description):

RSpec.describe “Creating Comment”, type: :feature, js: true do

context "user submits a reply to a comment on an article” do

it “shows the reply on the article’s page” do

end

end

end

If an abstraction does not give you the slightest clue of what it is doing without looking at its content, Then it is a pretty poor abstraction. When a test is full of distracting details, simply moving the details behind methods is not necessarily an improvement; careful thought must be given to what abstractions the methods represent and why they are helpful.

RSpec.describe "Creating Comment", type: :feature, js: true do

before { sign_in user }

it "User replies to a comment" do

create_setup_data

submit_comment

expect_correct_comment

end

def create_setup_data

let(:user) { create(:user) }

let(:raw_comment) { Faker::Lorem.paragraph }

let(:article) do

create(:article, user_id: user.id, show_comments: true)

end

end

def submit_comment

create(:comment, commentable_id: article.id, user_id: user.id)

visit article_path.to_s

find(".toggle-reply-form").click

find(

:xpath,

"//div[@class='actions']/form[@class='new_comment']/textarea"

).set(raw_comment)

find(

:xpath,

"//div[contains(@class, 'reply-actions')]/input[@name='commit']"

).click

end

def expect_correct_comment

expect(page).to have_text(raw_comment)

end

end

The author also speaks about scoping (arranging app’s files) and gives a relevant example of an appointment model

ls -1 spec/models

appointment_spec.rb

invoice_spec.rb

patient_spec.rb

user_spec.rb

ls -1 app/models

appointment.rb

invoice.rb

patient.rb

user.rb

The rails g scaffold appointment command gave the developers to containers to put stuff in, one called app/models/appointment.rband another called spec/models/appointment.rb. Slowly over time, each of these containers group, a few lines of code at a time, into a monster.

How do we fix this? by slicing up the model code into a smaller, more cohesive pieces for instance:

The recurrence logic moved into an object called RecurrenceRule which lives in app/models/recurrence_rule.rb or even better with namespace Schedule::RecurrenceRule and lives at app/models/schedule/recurrence_rule.rb

Cohesion

If a code base is like a story, a file in a code base is perhaps like a chapter in a book. A well-written chapter will clearly let the reader know what the most important points are and will feature those important points most prominently. A chapter is most understandable when it principally sticks to just one topic.

If a detail would pose too much of a distraction or an interruption, it gets moved to a footnote or appendix or parenthetical clause.

A piece of code is cohesive if a) everything in it shares one single idea and b) it doesn’t mix into incidental details with essential points.

How cohesion gets lost

Fresh new projects are usually pretty easy to work with because when you don’t have very much code, it is easier to keep your code organized and when the total amount of code is small, things have to be pretty disorganized in order for it to hurt.

Things get tougher as the project grows. Entropy is the tendency for all things to decline to disorder unavoidably sets in.

A common manifestation of entropy is when I developer is tasked with adding a new behavior. he or she goes looking for the object that seems like the most fitting home for that new behavior. he or she adds the new behavior, which does not perfectly fit the object where it was placed, but the code only makes the object say 5% less cohesive, the result of all these changes in aggregate is a surprisingly bad mass.

How cohesion can be preserved?

The first key to maintaining cohesion in any particular piece of code is to make a clear distinction between what’s essential and what’s incidental.

Let’s say that I have for example a class called Appointment. The concerns of Appointment include among other things, start time, a client and some matters related to caching.

I would say that the start time and client are essential concerns of an appointment and that the caching is probably incidental.

Now where to put these newly sprouted files. The rationale here is that cashing logic will only ever be relevant to a scheduling whereas an appointment might be viewed in multiple contexts, for example sometimes scheduling and sometimes billing.

app/models/appointment.rb

app/models/scheduling/appointment_caching.rb

Here is another example of a Customer object with certain method including one called balance. Over time the balance calculation becomes increasingly complicated to the point that it causes Customer to lose cohesion. I can just move the guts of the balance method into a new object (a PORO) called CustomerBalance and delegate all the gory details of balance calculation to that object. Now the Customer object once again focuses on the essential points and forget about the incidental details.

app/models/customer.rb

app/models/billing/customer_balance.rb

In the case that we cannot extract the incidental details of an object we can use a ‘mixin’ instead. I view ‘mixin’ as a good way to hold a bit of code which has cohesion with itself but which does not quite qualify as an abstraction and so does not make sense as an object. For me, ‘mixins’ usually don’t have a standalone value, and they are usually only ever “mixed in” to one object as supposed to be reusable.

I could have said ‘concern’ instead of ‘mixin’, but to me it is a distinction without a meaningful difference, and concerns come along with some conceptual baggage that I don’t want to bring into the picture here.

Jason believes in organizing files by meaning rather than type.

Shared examples from our spec is something that at first glance seems to be a good idea however it provides obfuscation because it is difficult for the programmer to know where the values and variables come from https://rspec.info/features/3-13/rspec-core/example-groups/shared-examples/

Duplication is mainly bad when it passes a risk of two or more pieces of behavior getting out of sync due to a mistake, leaving one copy of the behavior correct and the other one incorrect. Since tests are not behavior, they are not always susceptible to the same kinds of duplication mistakes as application code.

Test helpers on DRY

That DRY principle does not apply to test code in the same way that it applies to application code, since application code is behavior whereas the test code is a specification. Helpers are not tested and they do not contain specifications. They simply help with gruntwork. online test code a helper does benefit from being DRY just like application code does.

Managing setup data

Most tests require some setup data, the more setup data there is, the harder it is to keep the test code understandable.

It’s important for tests to be deterministic, meaning that they behave the same way every time. if a test is not deterministic, it may pass sometimes and fail sometimes, giving false negatives and causing numbness to legitimate failures.

A key ingredient in making a test stick is to start with the same state every time. If a test is allowed to pollute its environment by changing for example environmental variables, configuration settings or database data, then the test that runs after it will run in a fould environment instead of a clean slate.

For this reason, Rails by default runs every test inside of the database transaction, before the test finishes, the transaction gets aborted so that any data created inside the test never gets committed to the database.

Every piece of data that’s in the database when test starts, we will call this data “background data”, has the potential to influence how the test behaves. the less background data there is, the fewer headaches it can cause.

Naming.

The author lays out a test that has three values: ‘user’, ‘token’, ‘mismatch_token’. He states that the last one is pretty clear, however after reading the whole test he suggested changing from ‘token’ to ‘valid_token’ in order to make it clearer.

A good rule of thumb for naming is to call things what they are. This rule may sound obvious, but how many times have you encountered a variable method, class or database table that’s named according to something other than what it actually is?

Because code is read many more times than it is written, the cost of a poor name is often many times more than the cost saved by skipping the effort of giving it a clear name.

One topic per test.

Some testers believe that each test should have just one assertion, others believe that this rule is hogwash, and that a test should have as many assertions as it needs. The significant thing about the test is not how many assertions it contains but rather how many topics it contains.

A test with just one topic – a test that’s only about one thing– it’s going to be easier to understand than a test that conflates multiple topics.

It is common for developers to stuff several assertions into one test out of a desire for performance efficiency, especially in system specs, which are expensive to run. That I think this is usually a false economy. Yes, a performance benefit is cheap but at expense of understandably but the savings in CPU time is paid for by engineer time and we of course know which of the two is more expensive.

The phases of a test

Every test has four phases: set up, exercise, assertions and tear down. in Rails the tear down usually happens automatically, so we only need to think about the ‘setup’, ‘exercise’ and ‘assertion’ steps done. They are also known as a range, act, assert.

Organizing your test Suite.

As we saw at the beginning of this chapter, a test suite, when thought of as a structure set of behavior specifications, can serve as the backbone of a systems design. The files and folders in a test suit should be laid out in an orderly and logically fashion so that when one needs to find something, it can be found easily.

Instead of organizing tests by test type, which in a sense is an incidental detail, I find it more logical to organize my test by domain concept. Each folder in a test suite can be thought of as having two dimensions: to what domain concept it belongs and to what type of test it pertains.

Traditional Rspec way to order files:

| billing | schedule | clinical

----------|----------------|----------------|----------------

models | models/billing | models/schedule | models/clinical

requests | requests/billing | requests/schedule | requests/clinical

system | system/billing | system/schedule | system/clinical

Jason suggests the following by meaning (domain-specific) and then type:

| models | requests | system

----------|---------------|----------------|---------------

billing | billing/models | billing/requests | billing/system

schedule | schedule/models | schedule/requests | schedule/system

clinical | clinical/models | clinical/requests | clinical/system

Lastly, something helpful that this new approach helps is to catch regressions, when tests are organized by the main concept, the search for regressions can be conducted much more logically and efficiently. Once you get for instance spec/schedule/appointments/system/cancel _appointment.rb passing, you can then locally run all the tests in that parent folder spec/schedule/appointment.

Chapter 6. Duplication in test code.

It is commonly believed that duplication is code that appears in two or more places. But this is actually mistaken. Duplication is when there is a single behavior that’s specified into or more places.

Just because two identical pieces of code are present does not necessarily mean duplication exists. And just because there are no two identical pieces of code present doesn’t mean here is no duplication.

Two pieces of code could happen to be identical, but if they actually serve different purposes and lead separate lives, then they do not represent the same behavior, and they do not constitute duplication.

The way to tell if two pieces of code are duplicative is not to see if their code matches. The question that determines application is; “if I changed one piece of code in order to meet any requirement, would it be logically necessary to update the other piece of code the same way?”

The main reason for duplication is that it leaves a problem susceptible to developing logical inconsistencies. If a behavior is expressed in two different places in a program, and one of them accidentally does not match the other, then the deviating behavior is necessarily wrong.

Another reason duplication can be bad is because it can cost an extra maintenance burden.

What determines how risky duplication is 1) one how easily noticeable the duplication is 2) how much extra maintenance overhead the presence of the duplication incurs, 3) how much traffic that area receives( how frequently that area of code needs to be changed or understood)

Noticeability

If someone updates one of the code of the behavior to meet any requirement they are very likely to miss updating the other one. We might call this the proximity factor.

If two pieces of duplicated behavior appear in different files in different areas of the application, then a mess is much likely to occur, and therefore the application processes a larger risk.

Another quality that makes the noise ability of the application issued is similarity. If two pieces of code look very similar than the duplicity is more likely to be noticed than if the two pieces of code do not look the same (similarity factor)

Maintenance overhead

If a piece of duplication exists as a part of the database schema, that’s a much higher maintenance cost than a small duplication in code. Instances of duplication there are large and are not represented by identical code can also be costly to maintain because, in those cases, you cannot just type the same thing twice, you have to perform a potentially expensive translation step in your head.

Traffic level The more frequently the code is changed, the more of a toll it is going to incur, and so the bigger problem it is.

Another tollway is when a piece of code needs to be understood as a priority to understanding a different piece of code.

How to decide whether to DRY up a piece of code. There are two simple options, although it is not always easy.

Severity. If a piece of duplication is severe for example it has low noticeability, it posses high maintenance overhead, and has a high traffic level, then those all add weight to the argument that the duplication should be cleaned up.

The quality of alternatives just because a piece of duplication costs something does not automatically mean that the duplicated version costs less. It doesn’t happen very often but sometimes ad duplication unavoidably results in code that’s so generalized that it is virtually impossible to understand.

Rule of three, write everything twice. When I’m deciding whether to dry up a duplication, I asked myself: how severe is this instance of duplication? Are we able to come up with a fix that’s better than the duplicated version and not worse?

Example, imagine a piece of duplication in the form of three very simple and nearly identical lines, group together in a single file, the file is a unimportant one which only gets touch a couple of times a year, and no one needs to understand that piece of code as a prerequisite to understanding anything else.

Now imagine another piece of duplication. The duplication appears in only two places but the places are distant from each other and therefore the application is hard to notice. The two places where the duplicated behavior appears are expressed differently enough that the code would elude detection by a quality tool or a manual human search. The behavior is vitality central and important one and the two places the behavior appears are virtually painful to keep in sync.

Duplication is cheaper than the wrong abstraction

The real difference between duplication and test code and application code. Duplication, again, is when a one behavior is expressed into or more places. The difference between the test code and application code is that test code does not contain behavior. all the behaviors are in the application code. the purpose of the test code is to specify the behaviors of the application code.

What is the codebase that determines whether the application code is correct? the test.

If a piece of behavior is duplicated in two places in the application code and one piece of behavior gets changed, it does always logically follow that the other piece of behavior needs to get updated to match. (otherwise they will not be the instance of a duplication.)

Chapter 7. Mocks and stubs.

What is a stub?

In a football scrimmage, the team doesn’t play against a real opponent because:

- It’s expensive (travel, logistics, etc.).

- It could have unwanted side effects (injuries, revealing strategies, etc.).

- Instead, they simulate the opponent using their own players to control the scenario.

Similarly, in testing:

A stub replaces an actual method with a controlled response. It prevents expensive operations like:

- Database queries.

- External API calls.

- Complex calculations.

- It ensures the test has more controllable responses.

Example:

class PaymentGateway

def charge(amount)

# Imagine this calls an external API (expensive!)

"Charged #{amount}"

end

end

RSpec.describe PaymentGateway do

it "stubs the charge method" do

gateway = PaymentGateway.new

allow(gateway).to receive(:charge).with(100).and_return("Stubbed charge")

expect(gateway.charge(100)).to eq("Stubbed charge") # Controlled response

end

end

What is a mock?

Imagine Mr. Boss pretends to be a regular customer (mock objects pretend to be real objects) He orders specific items like a hamburger, fries, and a coke (sets expected method calls).

Afterward, he “interrogates” the experience - “Did you receive the hamburger you ordered?” (verifies that expected interactions occurred) If any verification fails, the test fails

A mock is a fake object (like the undercover boss is a fake customer) It has predetermined responses

class Waiter

def take_order(order)

# Imagine this method interacts with a real kitchen system

"Order placed: #{order}"

end

end

RSpec.describe Waiter do

it "verifies that the order was placed" do

waiter = Waiter.new

expect(waiter).to receive(:take_order).with("hamburger")

waiter.take_order("hamburger") # If this isn't called, the test fails

end

end

Summary

-

A stub is like using a fake team in a football scrimmage—it avoids unnecessary costs.

-

A mock is like an undercover boss—it checks if expected interactions happen.

“Do I just need to fake a response?” → Use a stub.

“Do I need to verify that something was called?” → Use a mock.

| Feature | Stub | Mock |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Controls return values | Verifies method calls |

| Tracks calls? | No | Yes |

| Fails test if method is not called? | No | Yes |

Testing third party interactions using stubs

In principle we could test third party interactions by actually hitting live services. the upside to this approach is that it provides a very realistic environment, however the downsides are:

Loss of determinism, this means that our tests will potentially be non-deterministic. Determinism is the property of always behaving the same way given the same starting conditions. Tests that involve third-party services may behave one way on some runs and another way on other runs even though they’re starting conditions were the same.

Limited ability to control test scenarios, when writing tests that involved third-party services, it is desirable to cover certain scenarios such as when the server returns a value response, when the service return a graceful error response, or a 500 error so creating this scenario is impossible.

Side effects, using live services can also cause rate limiting, causing the test to eventually flake once requests start failing due to rate limits, and also preventing real production requests.

Stubbing services.

Stubbing third party services avoids the problems that come with using live services. When services are stubbed our test can be deterministic, we can control our test scenarios and we don’t have to worry about introducing side effects. What exactly is stubbing? is a practice of replacing one piece of behavior with another.

Coming up with good tests

A common mistake is to write tests that “make sure the API gets called” and to “make sure the right results get returned”. Remember that testing is about a specification, not verification. The test is not to “make sure the code worked” but rather to specify how the code should work.

Remember that the behavior we are interested in is what happens after the API (stripe, paypal) response is received.

Example of code before “stubbing”

require "rails_helper"

include APIAuthenticationHelper

RSpec.describe "GitHub tokens", type: :request do

Describe “POST /api/v1/github_tokens” do

it "returns a token" do

post(

api_v1_github_tokens_path,

headers: api_authorization_headers

)

expect(response.body).to be("ABC123")

end

end

After stubbing:

require "rails_helper"

include APIAuthenticationHelper

RSpec.describe "POST /api/v1/github_tokens", type: :request do

it "returns a token" do

allow(GitHubToken).to receive(:generate).and_return("ABC123") 👈

post(

api_v1_github_tokens_path,

headers: api_authorization_headers

)

expect(response.body).to eq("ABC123")

end

end

The behavior we are mainly interested in is not how the token gets generated but in how the GitHub tokens API endpoint response to a request for a token.

The line “allow(GitHubToken)” Does not actually call the method, but instead return the hard coded value “ABC123”.

Code example for mocking

class TaskProcessor

def self.process

puts "Processing task..."

end

end

class BackgroundJob

def perform

TaskProcessor.process

end

end

def start_background_job(job = BackgroundJob.new)

job.perform

end

class MockedJob

def initialize

@performed = false

end

def perform

TaskProcessor.process

@performed = true

end

def performed?

@performed

end

end

RSpec.describe "Starting the background job with RSpec mock" do

it "calls .perform on the mock job" do

job = MockedJob.new 👈

expect(job).to receive(:perform) 👈

start_background_job(job)

end

end

Chapter 8. Flaky tests.

When a boat leaks, the crew has not one problem but two. One problem is the water that’s in the boat, causing it to lose buoyancy. This problem can be mitigated by bailing out water, but it won’t solve the other problem, which is that there are holes in the boat allowing more water to leak in.

| Layer | Symptom | Root cause |

|---|---|---|

| Secondary | Water in the boat | Holes in the boat. |

| Primary | Holes in the boat | Poor design? Aging? |

The holes in the boat are the symptom of the primary problem.

The two layers of the flaky test problem

| Layer | Symptom | Root cause |

|---|---|---|

| Secondary | Individual flaky tests | Instances of non-determinism (race conditions, environment corruption, randomness, external dependencies in tests, fragile time dependencies) |

| Primary | Instances of non-determinism (race conditions, environment corruption, randomness, external dependencies in tests, fragile time dependencies) | Application complexity, poor test design. |

What is a flaky test?

A flaky test is a test that passes sometimes and fails sometimes even when no code has changed. Flaky test cost test runs to fail illegitimately, causing annoyance, wasted time and a numbness to legitimate failures. All flaky tests are caused by some form of non-determinism.

Code that’s deterministic is code that always gives the same output for a given input. Flaky tests are caused by some form of non-determinism.

Race conditions

Race conditions are most likely to arise when the buffer is small. Imagine, a guy arrives at the train station with only a 1-minute buffer. If a ticket machine is slow or a gate malfunctions, he misses the train. Similarly, in software, race conditions occur when timing issues cause unpredictable failures.

This gets fixed by adding an expect(page).to have_content command immediately after the command that submits in this case the form. Unlike the indifferent click_on command expect_page.to have_content will wait a bit before it gives up and allows the test Runner to continue.

click_on “submit”

expect(page).to have_content(“Thanks”) # to prevent race conditions

click_on “Home”

You can modify the default wait time docs

Capybara.default_max_wait_time = 10

And also per-test basis

Capybara.using_wait_time(10) do

expec(page).to have_content(“Success”)

end

Environment state corruption

Imagine two tests, each of which creates a user with email_address: test@example.com the first test will pass and, if there is a unique constraint on user.email, the second test will raise an error due to unique constraint validation. Sometimes the first test will fail and sometimes the second test will fail depending on the order in which order you run them.

Another way to spoil the environment is to change a configuration setting. Let’s say you have a test environment with a background job configured not to run for most tests because most background jobs are irrelevant to what’s being tested and would just slow things down. But then let’s imagine that you have one test that you do want background jobs to run, and so at the beginning of the test you set background job setting from the don’t run to run. if you don’t remember to change the setting back to don’t run at the end all background jobs will run for all later tests and potentially cause problematic behavior.

External dependencies in tests.

The way to prevent flaky test caused by network dependencies is to stub services rather than hitting live services

Randomness

By definition common non-deterministic. If you have for example a test that generates a random integer between one and two and then asserts that the number is one that is going to fail about half the time period.

Fragile time dependencies in test

The way around this problem is to always use absolute times in tests instead of relative ones. For instance “2025-03-10 08:00:00” Instead of “tomorrow 12:00 p.m.”

| Problem | Prerequisite |

|---|---|

| Race conditions | Concurrency |

| Environment state corruption | Mutable environment state |

| Randomness | Randomness |

| External dependencies | External dependencies |

| Fragile time dependencies | Features that involve time |

To summarize all this in a few words, complicated applications tend to have more flaky tests than simple ones.

How to fix flaky tests

Flaky tests are hard to fix largely because they are hard to reproduce. If a flaky test cannot be consistently reproduced then it is very hard to hypothesize about the conditions to make it fail.

It is also hard to hypothesize about the case of a flaky chest if we don’t have enough background knowledge to guide our hypothesis. If we are familiar with the conditions that can lead to flaky tests, then we can come up with much more intelligent guesses than if we are clueless about how flaky tests arise.

The fact that flaky tests are hard to reproduce also means that our fixed attempts are hard to validate or invalidate.

Adopt an effective bug fix methodology.

I find it helpful to split the bug fix process into three distinct stages:

- reproduction,

- diagnosis and

- fix.

When fixing a bug it is very easy to let your head get filled with a jumble of thoughts and lose track of what you’re doing. Dividing the processing to steps helps us stay focused on one activity at the time.

Arm yourself with background knowledge. All about diagnosis start as guesses to get more efficient in diagnosing flaky tests, commit to five causes of flaky tests to memory.

Before reproducing: determine whether it is really a flaky test. Not everything that appears to be a flaky test is actually a flaky test. Sometimes a test that appears to be flaky is just a healthy test that’s legitimately failing.

Reproducing a flaky test. My go-to method for reproducing a flaky chest is simply to re-run the test suite multiple times on my CI service until I see the flaky test fail. I like to run the test so it’s a large number of times to not only reproduce the failure but also to get a feel for how frequently the flaky test fails.

Diagnosing flaky tests. Remember that if you preferably understood all the code and tests, you would also understand the cause of the flaky test that you are trying to diagnose. All that lies between you and a diagnosis is certain amount of understanding.

Applying the fix for a flaky test. Sometimes the only way to see if a flaky test is fixed with our attempt is to wait.

Do not delete a test without a good reason. Remember that the important thing is not the cost benefit ratio of an individual flaky test fixed, but the cost benefit ratio of all the flaky test fixes on average. This means that fixing flaky tests creates a positive feedback loop.

Chapter 9. Testing sins and crimes.

Chapter 10. Ruby DSL.

Chapter 11. Factory bot.

Chapter 12. RSpec syntax.

Chapter 13. Capybara’s DSL.

Details

- Professional Rails Testing by Jason Swett.

- Published: 2024