dom lizarraga

POOD Session 9: Loosen Coupling, Find Shameless Green & Vary the Bits

Session 9: Vary Verse

Date: October 04, 2025

This blog post consists in three parts:

- My notes on Loosen Coupling

- My notes on Find Shameless Green

- My notes on New requirement: Vary the Bits

Key Concepts

Loosen Coupling

Watch 1: Choosing Which Units to Test

Unit tests are tests of just a single class (Bottles, BottleNumber) and an integration test is a test that checks the collaboration of more than one single class (APIs, db interaction).

The initial tests that we wrote back in Chapter 2 were unit tests to begin with because we just had that single Bottles class, and now they are badly out of date and they’ve long since been turned into integration tests.

The rule is every class should have a unit test.

All of these classes are being covered by the original tests that were unit tests but are now integration tests, and some of these new objects need their own unit tests now.

We think of tests as something that prevents regressions, as a way to prove that our code works correctly and to keep us from accidentally breaking things.

- Also, tests tell the story of the code.

- Tests help to expose the design of the code that you have, if the code is poorly designed it will be difficult to test.

You can write incorrect, misleading tests around well-designed code. However, the converse isn’t really true. It’s really hard to write nice, neat, intention revealing tests around code that is poorly designed.

You can think of tests as the first reuse of your code.

When you write tests last, it’s very common to find that is really difficult to test your code, and the reason is, it’s very easy when you’re just writing code to get a bunch of tight coupling, to have a bunch of objects that know way too much about each other such that they can only be used in combination with each other.

If you’re a test last kind of person, you just go beat on your tests until you make them work, no matter how painful it is, and you leave that entangled mess as a consequence for other people downstream.

I promise you, that if you wrote tests first, you would not do this. It’s too much trouble.

This is an argument for writing tests first. If you write them first, you will refuse to put up with tightly-coupled code; you’ll design your code so that testing is easy.

If you write the code first and put the tests last, no matter how difficult it is to get the tests running, you’ll probably keep the code and just write those tests.

Wirting tests for BottleNumber0, BottleNumber1, BottleNumber6 is not worth the time, it wont save money and Sandi suggested to test the whole BottleVerse class instead.

Watch 2: Reorganizing Tests

We should strive to write the fastest tests possible, the fewest of them, with the most intention revealing expectations, and the least amount of code.

The fact that BottleVerse and BottleNumber are hidden is also a factor that don’t require testing. On the other hand we have Bottle that gets injects BottleVerse which means it’s a public relationship, it deserves testing.

# public relationship and loose coupling between Bottle and BottleVerse

# it makes BottleVerse independent of context and suggest it should have unit test

class Bottles

attr_reader :verse_template

def initialize(verse_template: BottleVerse) 👈

@verse_template = verse_template

end

...

# not public relationship and tight coupling between BottleVerse and BottleNumber

class BottleVerse

def self.lyrics(number)

new(BottleNumber.for(number)).lyrics

end

...

We started by creating a BottleVerseTest and move one by one of BottlesTest, we re-run test to see if something fails and changed the class initialized, instead of BottlesTest we created BottleVerseTest.

Another change was the verbose test name, here we want to be very explicit and reduce the uncertainty that a vague name could cause for future readers

class BottleVerseTest < Minitest::Test

def test_verse_general_rule_upper_bound

expected = "99 bottles of beer on the wall, " +

"99 bottles of beer.\n" +

"Take one down and pass it around, " +

"98 bottles of beer on the wall.\n"

assert_equal expected, BottleVerse.lyrics(99)

end

def test_verse_general_rule_lower_bound

expected = "3 bottles of beer on the wall, " +

"3 bottles of beer.\n" +

"Take one down and pass it around, " +

"2 bottles of beer on the wall.\n"

assert_equal expected, BottleVerse.lyrics(3)

end

def test_special_verse_2

expected = "2 bottles of beer on the wall, " +

"2 bottles of beer.\n" +

"Take one down and pass it around, " +

"1 bottle of beer on the wall.\n"

assert_equal expected, BottleVerse.lyrics(2)

end

def test_special_verse_1

expected = "1 bottle of beer on the wall, " +

"1 bottle of beer.\n" +

"Take it down and pass it around, " +

"no more bottles of beer on the wall.\n"

assert_equal expected, BottleVerse.lyrics(1)

end

def test_special_verse_0

expected = "No more bottles of beer on the wall, " +

"no more bottles of beer.\n" +

"Go to the store and buy some more, " +

"99 bottles of beer on the wall.\n"

assert_equal expected, BottleVerse.lyrics(0)

end

end

Watch 3: Seeking Context Independence

Context of an object is, its surroundings. It’s the stuff that’s around it, the things that it needs in order to be able to do its own job. Objects that require lots of context, large numbers of other things, are difficult to reuse in new contexts.

Objects that have less context, that require fewer things from their surroundings, are more reusable in other situations.

If we look at the Bottle class and because we went over several refactoring where we extracted and isolate some bit of code we do know why it’s called Bottle but someone new might not know why therefore here is a new proposal to rename it. And given the fact that the song always goes downwards, like 15, 14, 13, 12, 11 and so on.

The first step is to copy/paste the Bottle class and rename the duplicate with CountdownSong and pass that new name to tests, re-run test and see that nothing breaks

class CountdownSong

attr_reader :verse_template

def initialize(verse_template: BottleVerse)

@verse_template = verse_template

end

...

With this change the tests now seem awkward, like off of what the new name reflects, and that made the more context independent. We need to do something with the tests to tell a better story about what CountdownSong actually does.

Think of it from a reader point of view, where it’s easy to read, where it really shows CountdownSong behavior. The next test is a story we would like to have, it doesn’t work yet.

# bottles_test.rb

class CountdownSongTest < Minitest:Test

def test_a_couple_of_tests

expected =

"This is verse 99.\n" +

"\n" +

"This is verse 99.\n" +

"\n" +

"This is verse 97.\n"

assert_equal(

expected, CountdownSong.new.verses(99, 87))

...

If we write the code first, then we can start working on making it work with our code. What we need is another verse_template that would play as a test_double in RSpec.

New version more intention revealing for test_a_couple_of_tests

class VerseFake

def self.lyrics(number)

"This is verse #{number}.\n"

end

end

class CountdownSongTest < Minitest:Test

def test_a_couple_of_tests

expected =

"This is verse 99.\n" +

"\n" +

"This is verse 99.\n" +

"\n" +

"This is verse 97.\n"

assert_equal(

expected, CountdownSong.new(verse_template: VerseFake).verses(99, 87))

...

Side node: we should not use pattern names in class names, for instance, inestead of NumberDecorator we used BottleNumber which is more revealing of the purpose. It’s a failure of naming. We should be careful with decorator, fake, wrapper, adapter and facade.

The current public API of CountdownSong has song, verses() and verse and we still need to test the verse mehtod:

class CountdownSongTest < Minitest:Test

def test_verse

expected = "This is verse 500.\n"

assert_equal(

expected, CountdownSong.new(verse_template: VerseFake).verses(500))

end

def test_verses

expected =

"This is verse 47.\n" +

"\n" +

"This is verse 46.\n" +

"\n" +

"This is verse 45.\n" +

"\n" +

"This is verse 44.\n" +

"\n" +

"This is verse 43.\n"

assert_equal expected, CountdownSong.new(verse_template: VerseFake).verses(47,43)

end

def test_verses

expected =

"This is verse 99.\n" +

"\n" +

"This is verse 99.\n" +

"\n" +

"This is verse 97.\n"

assert_equal(

expected, CountdownSong.new(verse_template: VerseFake).verses(99, 87))

...

Lastly, the method song in chapter 2 we had to write down all 100 cases for the song due to the code design, remember it’s hardcoded song(99, 0) so it’s time to extract and add them as argument in the CountdownSong

class CountdownSong

attr_reader :verse_template, :max, :min

def initialize(verse_template:, max: 99999, min: 0)

@verse_template = verse_template

@max = max

@min = min

end

def song

verses(max, min)

end

def verses(upper, lower)

upper.downto(lower).map { |i| verse(i) }.join("\n")

end

def verse(number)

verse_template.lyrics(number)

end

end

Here is the text for the song method, it has prime numbers (which means they’re meaningless, by convention) and now we can remove the big test.

def test_song

expected =

"This is verse 23.\n" +

"\n" +

"This is verse 22.\n" +

"\n" +

"This is verse 21.\n" +

"\n" +

"This is verse 20.\n" +

"\n" +

"This is verse 19.\n"

assert_equal expected, CountdownSong.new(verse_template: VerseFake, max: 23, min: 19).song

end

Watch 4: Communicating With the Future

We’re almost done and the code looks good. We still need to send signals for future readers. One of those signal systems is shape. The shape arrage -> act -> assert pattern.

That pattern means you set up an expectation, and then you do something, and the you check if the result of that thing you did met that expectation.

If all of the tests you have written have a specific shape, and the one doesn’t it will cause a mental jolt on the reader and they’ll wonder what’s the difference?

The objective is to have all the tests with same shape so that nothing is indicating to the readers by the shape.

Another topic is dynamic typing, Ruby is awesome and not being statis typed gives you freedom, however the price you pay for the freedom is that it’s on your head to make sure that when you inject an object into a class, where you have a number of choices of actual classes that you can inject, you pick some role player and inject it, “the receiver” has to be able to trust that that object plays the role it’s supposed to play. The compiler would prevent it.

Above idea provokes a Liskov violation, where you implement an if conditional in order to check the type and know what message should be sent or what API use.

Therefore, you need to make sure that all the objects that appear to play a role really do so, such that some other object that’s interacting with one of those role playing objects can treat them all as if they’re interchangeable so that you do not have to say “What kind of thing are you?” in order to know how to talk to them, you have to get this right yourself. There’s a couple of different ways to make this happen.

- You can just tell everybody “Everything that says it’s a

verse_templatehas to play the role ofverse_template.”, which means it needs to respond tolyrics.

That means, in the case of our code, that BottleVerse and VerseFake have to both respond to lyrics and everybody, if they make a new one, or if they use them, or if they change them, they need to honor that contract.

-

Use a library that help you with types like Sobet. This will help define a common interface and then make all the objects conform to the interface

-

Write tests to prove that objects that play a common role conform to their API, and that’s what we’re about to do here.

# bottles_test.rb

module VerseRoleTest

def test_plays_verse_role

assert_respond_to @role_player, :lyrics

end

end

class VerseFake

def self.lyrics(number)

"This is verse #{number}.\n"

end

end

class VerseFakeTest < Minitest::Test

include VerseRoleTest

def setup

@role_player = VerseFake

end

end

Sandi’s summary of this block:

Tests help prevent errors in code, but to characterize them so simply is a disservice; they offer far more. Good OO is built upon small, interchangeable objects that interact via abstractions. The behavior of each individual object is often quite obvious, but the same cannot be said for the operation of the whole. Tests fill this breach.

Object-oriented applications rely on message sending. The key virtue of messages is that they add indirection. Messages allow the sender to ask for an abstraction and be confident that the receiver will use the appropriate concrete implementation to fulfill the request. Senders are responsible for knowing what they want, receivers, for knowing how to do it. Separating intention from implementation in this way allows you to introduce new variations without altering existing code; simply create a new object that responds to the original message with a different implementation.

When designed with the following features, object-oriented code can interact with new and unanticipated variants without having to change:

-

Variants are isolated. They’re usually isolated in some kind of object, often a new class.

-

Variant selection is isolated. Selection happens in factories, which may be as simple as isolated conditionals that choose a class.

-

Message senders and receivers are loosely coupled. This is commonly accomplished by injecting dependencies.

-

Variants are interchangeable. Message senders treat injected objects as equivalent players of identical roles.

Initially, this reliance on abstractions and indirection increases the complexity of code. What OO promises in return is a reduction in the future cost of change. Highly concrete, tightly coupled code will resist tomorrow’s change. Code that depends on loosely coupled abstractions will encourage it.

Because tests need to execute code, they supply early and direct information about inadequate design, and they provide impetus and inspiration for refinements. When tests are difficult to write, require lots of setup, or can’t tell a satisfying story, something is wrong. Listen. Fixing problems now is not only cheaper than fixing them later, but will improve your code, clarify your tests, and make glad your work.

Find Shameless Green

Here we started a brand new problem called “The House that Jack built”.

This time I searched what that song was about in comparison to the first time I faced “99 bottles”

Here is a small research:

Definition: A traditional English cumulative rhyme that builds layer by layer — each verse adds a new element while repeating all the previous ones.

Verse 1: This is the house that Jack built.

Verse 2: This is the malt That lay in the house that Jack built.

Verse 3: This is the rat, That ate the malt That lay in the house that Jack built.

Verse 4: This is the cat, That killed the rat, That ate the malt That lay in the house that Jack built.

Watch 1: Finding Shameless Green

We are tasked to write the first version of code that satisfies tests, remember reaching green as soon as possible is the goal, aiming for understability rather than changeability.

My frist version of the code:

class House

def line(number)

case number

when 1

"This is the house that Jack built.\n"

when 2

"This is the malt that lay in the house that Jack built.\n"

when 3

"This is the rat that ate the malt that lay in the house that Jack built.\n"

when 4

"This is the cat that killed the rat that ate the malt that lay in the house that Jack built.\n"

when 5

"This is the dog that worried the cat that killed the rat that ate the malt that lay in the house that Jack built.\n"

when 6

"This is the cow with the crumpled horn that tossed the dog that worried the cat that killed the rat that ate the malt that lay in the house that Jack built.\n"

when 7

"This is the maiden all forlorn that milked the cow with the crumpled horn that tossed the dog that worried the cat that killed the rat that ate the malt that lay in the house that Jack built.\n"

when 8

"This is the man all tattered and torn that kissed the maiden all forlorn that milked the cow with the crumpled horn that tossed the dog that worried the cat that killed the rat that ate the malt that lay in the house that Jack built.\n"

when 9

"This is the priest all shaven and shorn that married the man all tattered and torn that kissed the maiden all forlorn that milked the cow with the crumpled horn that tossed the dog that worried the cat that killed the rat that ate the malt that lay in the house that Jack built.\n"

when 10

"This is the rooster that crowed in the morn that woke the priest all shaven and shorn that married the man all tattered and torn that kissed the maiden all forlorn that milked the cow with the crumpled horn that tossed the dog that worried the cat that killed the rat that ate the malt that lay in the house that Jack built.\n"

when 11

"This is the farmer sowing his corn that kept the rooster that crowed in the morn that woke the priest all shaven and shorn that married the man all tattered and torn that kissed the maiden all forlorn that milked the cow with the crumpled horn that tossed the dog that worried the cat that killed the rat that ate the malt that lay in the house that Jack built.\n"

else

"This is the horse and the hound and the horn that belonged to the farmer sowing his corn that kept the rooster that crowed in the morn that woke the priest all shaven and shorn that married the man all tattered and torn that kissed the maiden all forlorn that milked the cow with the crumpled horn that tossed the dog that worried the cat that killed the rat that ate the malt that lay in the house that Jack built.\n"

end

end

def recite

(1..12).map { |number| line(number) }.join("\n")

end

end

This time, first i search more about the domain, then started coding one test at the time until it met criteria and lastly I tried different solutions for the loop from String.new with << or .prepend() but this one worked.

I know that it’s going to be different from Sandi’s answer but I tried to aim for understability.

…

WOW! it look quite the same!! I was about to start interpolating like the last time since I noticed the pattern in each sentence but I resisted to make the premature abstraction !

Writing Shameless Green in the simplest possible way is not a commitment to keeping Shameless Green, but remember that if you get to green quickly, you’ll have green tests and you can write more complicated code using refactorings.

New requirement: Vary the Bits

Current lesson gives you a chance to practice:

- following the Open/Closed Principle

- choosing the most related Code Smell

- selecting the correct refactoring recipe

- writing the code.

Someone tells you that have a great idea that will change the output of the current code.

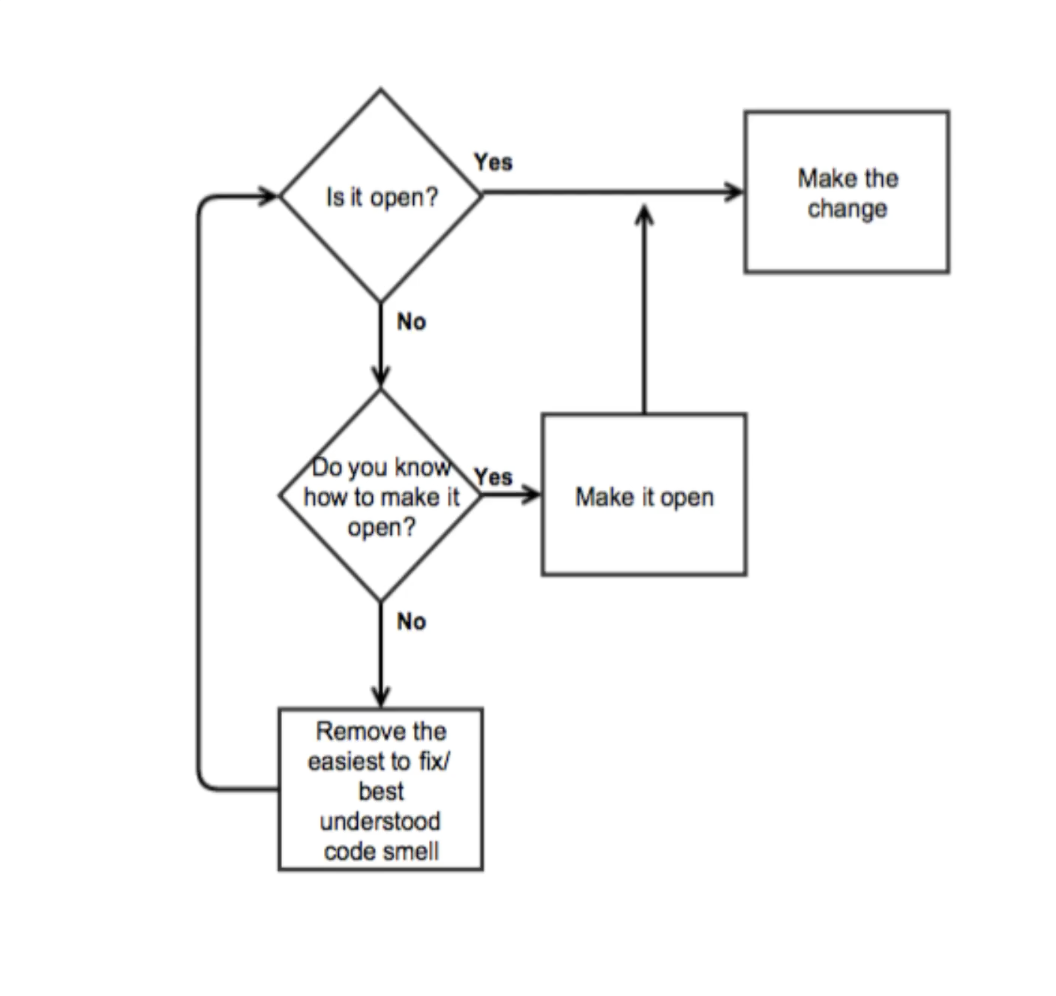

The first thing you’re going to do is think about that “flowchart”, where you ask yourself, “Is this code ‘open’ to the new requirement?” And the answer to that is ‘no’, this code isn’t open to changing the little bits in all these lines.

Then, you know how to make it open? The answer is no. Mostly every time the first two answers are NO.

Let’s fall back to code smells !

And this code has many of the same code smells we solve in 99 Bottles like:

- magic number

- conditional code (checking for type value)

- long method

- code duplication

We’ll ignore conditional, and stay with magic number and code duplication.

“Which one of those is more closely related to the thing I’m trying to vary?”, it’s the duplication, so let’s work on that.

We have a recipe that lets us remove duplication, it allows us to turn difference into sameness and that’s the Flocking Rules.

- Flocking Rules – A systematic way to discover hidden abstractions by:

-

Selecting the most similar pieces of code (Find the things that are least different)

-

Finding the smallest difference between them

-

Making the simplest change to remove that difference

In this case we might argue that verse 11 and 12 have the most things in common or maybe 1 and 2, so you should ask yourself “Which one is simpler?”

And it’s immediately obvious that the simplest pair is 1 and 2, and that means that’s what you should work on.

First proposal:

class House

def recite

1.upto(12).collect {|i| line(i)}.join("\n")

end

def phrase(num)

if num == 1

""

else

"the malt that lay in "

end

end

def line(num)

case num

when 1..2

"This is #{phrase(num)}the house that Jack built.\n"

when 3

"This is the rat that ate the malt that lay in the house that Jack built.\n"

This one seems clever but if we add another branch for number 3 we’ll end up with same conditionals like original code, remember we are looking for an algorithm that handles all different variants and doesn’t contain any duplication and that will enable to treat everything the same.

Using some pattern matching skills we discovered that the slots of the phrases we are pluging in have more meaning that the string itself, they have the position in which they are going to be placed, therefore we can use to design the algorithm that handle varieties.

class House

def recite

1.upto(12).collect {|i| line(i)}.join("\n")

end

def phrase(num)

["the rat that ate", "the malt that lay in ", ""].last(num).join("")

end

def line(num)

case num

when 1..3

"This is #{phrase(num)}the house that Jack built.\n"

when 4

"This is the cat that killed the rat that ate the malt that lay in the house that Jack built.\n"

when 5

"This is the dog that worried the cat that killed the rat that ate the malt that lay in the house that Jack built.\n"

We can cotinue doing this one line at the time and running tests so we make sure we don’t break something.

This is the code we finished with:

class House

def recite

1.upto(12).collect {|i| line(i)}.join("\n")

end

def phrase(num)

[ "the horse and the hound and the horn that belonged to",

"the farmer sowing his corn that kept",

"the rooster that crowed in the morn that woke",

"the priest all shaven and shorn that married",

"the man all tattered and torn that kissed",

"the maiden all forlorn that milked",

"the cow with the crumpled horn that tossed",

"the dog that worried",

"the cat that killed",

"the rat that ate",

"the malt that lay in",

""].last(num).join(" ")

end

def line(num)

"This is #{phrase(num)}the house that Jack built.\n"

end

end