dom lizarraga

I read Effective testing with RSpec by Myron Marston and Ian Dees. on April 11, 2025

Review

Recently, I participated in a very competitive interview. When I submitted the code challenge, I felt my weakest area was the testing suite. Even though feedback was not available, being honest with myself and seeing some posts from the reviewers, I decided to dive deeper into testing.

I picked up books like Professional Rails Testing by Jason Swett, Hands-On Test Driven Development by Greg Donald, Effective Testing with RSpec by Myron Marston and Ian Dees and even attended a testing workshop by Lucian Ghinda.

I had practiced testing before, but I felt it was time to level up and get it closer to the same standard as the rest of my code.

Here are the notes, examples, and quotes that stood out to me while reading.

- Getting started with RSpec.

- From writing specs to running them.

- The RSpec way.

- Starting On the Outside: Acceptance Specs.

- Testing in isolation: Unit specs.

- Getting real: Integration specs.

- Structuring code examples.

- Slicing and dicing specs with metadata.

- Configuring RSpec.

- Exploring RSpec expectations.

- Matchers included in RSpec expectations.

- Creating custom matchers.

- Understanding test doubles.

Part I — Chapter 1. Getting Started.

Picture of the book!

Where should i put this testing heuristics Given-When-Then scenarios

The forward is written by Tom Stewart author of Understanding Computation And he expresses something that picked my curiosity:

After all, the big challenge of test-driven development is not knowing how to write tests, but knowing how to listen to them. For your tests to be worth the bites they are written in, they must be able to speak to you about how well the underlying program is designed and implemented and, crucially, you must be able to hear them. The words and ideas baked into RSpec are carefully chosen to heighten your sensitivity to this kind of feedback. As you play with its expressive little pieces you will develop a test for what a good test looks like, and the occasional stumble over a test that now seems harder or uglier or way more annoying than necessary will start you on a journey of discovery that leads to a better design for that part of your code base.”

In the introduction we see different quotes like our tests are broken again! Why does the suite take so long to run? What value are we getting from this test anyway? No matter whether you are new to automated tests or helping using them for years, this book will help you write more effective tests. by effective, we mean tests that give you more value than the time spent writing them.

This book you will learn RSpec in three phases:

Part I: Introductory exercises to get you acquainted with respect Part II: A work example spanning several chapters, so that you can see RSpecin action on a meaningful sized project Part III-V: A series of deep dives into specific aspects of RSpec, which will have you get the most out of RSpec

RSpec and behavior driven development:

RSpec bills itself as a Behavior Driven Development (BDD) test framework. I would like to take a moment to talk about our use of that term, along with the related term, Test Driven Development (TDD).

With TDD, you write each test case just before implementing the next bit of behavior. When you have a well written test, you wind up with more maintainable code. you can make changes with the confidence that your test suite will let you know if you have broken something.

It is about the way they enable fearless improvements to your design.

BDD brings the emphasis to where it is supposed to be: your code’s behavior.

RSpec is a productive Ruby test framework. we say productive because everything about it, its style, api, libraries, and settings are designed to support you as you write great software.

We have a specific definition of effective here, does this test pay for the cost of writing and running it? A good test will provide at least one of these benefits:

-

design guidance: helping you distill all those fantastic ideas in your head into running, maintainable code

-

safety net: finding errors in your code before your customers do

-

documentation:capturing the behavior of a working system to help it’s maintainers

As you follow along through the examples in this book, you will practice several habits that will help you test effectively:

When you describe precisely what you want your program to do, you avoid being too strict ( and failing when an irrelevant detail changes) or too lax (and getting false Confidence from incomplete tests).

By writing your specs to report failure at the right level of detail, you give just enough information to find the cause of the problem, without drawing in excessive output.

By clearly separating essential test code from noisy setup code, you communicate what’s exactly expected of the application, and you avoid repeating unnecessary detail.

When you reorder, profile, and filter your specs, you unearth order dependencies, slow tests and incomplete work.

Installing RSpec.

It is made of three independent ruby gems:

rspec-core: is the overall test harness that runs your specs.

rspec-expectations: provides a readable, powerful Syntax for checking properties of your code.

rspec-mocks: makes it easy to isolate the code you are testing from the rest of the system.

➜ rspec-book rbenv local 3.4.2

➜ rspec-book rbenv rehash

➜ rspec-book ruby -v

ruby 3.4.2 (2025-02-15 revision d2930f8e7a) +PRISM [arm64-darwin24]

➜ rspec-book bundle init

Writing new Gemfile to /Users/dominiclizarraga/code/dominiclizarraga/rspec-book/Gemfile

➜ rspec-book bundle add rspec

Fetching gem metadata from https://rubygems.org/...

Resolving dependencies...

Fetching gem metadata from https://rubygems.org/.

Fetching diff-lcs 1.6.2

Fetching rspec-support 3.13.4

Installing rspec-support 3.13.4

Installing diff-lcs 1.6.2

Fetching rspec-core 3.13.4

Fetching rspec-expectations 3.13.5

Fetching rspec-mocks 3.13.5

Installing rspec-core 3.13.4

Installing rspec-expectations 3.13.5

Installing rspec-mocks 3.13.5

Fetching rspec 3.13.1

Installing rspec 3.13.1

Note: The book suggests to use gem install rspec however I think it’s important to remember that, that command will install the library globally to that Ruby version so if you want to avoid that and narrow the impact that this installation may have, I suggest to create its own directory and use bundle init which will create a Gemfile and then you can add rspec gem to the Gemfile or use bundle add rspec. This will set this rspec version only to this project.

Let’s write our first spec 😁

The book starts with the very simple example of building a sandwich. What’s the most important property of a sandwich? the bread? the condiments? No, the most important thing about a sandwich is that it should taste good.

RSpec uses the words describe a it to express concepts in a conversational format:

- “Describe an ideal sandwich”

- “First, it is delicious”

01-getting-started/01/spec/sandwich_spec.rb

RSpec.describe “An ideal sandwich” do

it “is delicious” do

# developers work this way with RSpec all the time; they start with an outline and fill it in as they go.

end

end

Then let’s add the classes and methods

01-getting-started/01/spec/sandwich_spec.rb

RSpec.describe “An ideal sandwich” do

it “is delicious” do

sandwich = sandwich.new(“it’s delicious”, [])

taste = sandwich.taste

expect(sandwich). to eq(“it’s delicious”)

end

end

This file defines your test, known in RSpec as your specs, short for a specification (because they specify the desired behavior of your code). The outer describe block creates an example group – an example group defines what you are testing, in this case, a sandwich, and keeps related specs together.

The nested block, the one beginning with it, is an example of the sandwich’s use. As you write specs, you will tend to keep each example focused on one particular size of behavior you are testing.

This first paragraphs reminds me of Jason Swett’s book on how many times he stresses to the readers that tests are a specifications not validations! I was able to count at least 8 times that he mentions that for example: A specification is a statement of how some aspect of a software product should behave. Remember that testing is about a specification, not verification. A test suite is a structured collection of behavior specifications.

Differences between tests, specs and examples:

• A test validates that a bit of code is working properly. • A spec describes the desired behavior of a bit of code. • An example shows how a particular API is intended to be used.

In the bits of code that we wrote we can clearly see the pattern arrange/act/assert.

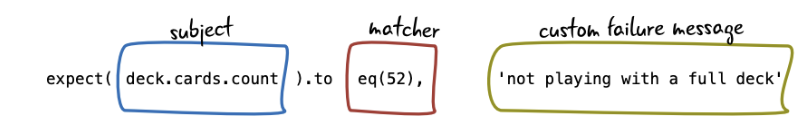

The last line with the expect keyword is the assertion in other test frameworks. Let’s look at the RSpec methods we’ve used:

• RSpec.describe creates an example group (set of related tests).

• it creates an example (individual test).

• expect verifies an expected outcome (assertion).

Up to this point this spec serves two purposes: documenting what your sandwich should do and checking that the sandwich does what it is supposed to. (Lovely, isn’t it? 🤌)

Let’s run the test and see what happens. (We’ll start reading common error tests)

$ ➜ rspec-book git:(master) ✗ bundle exec rspec 01-getting-started/01/spec/sandwich_spec.rb

F

Failures:

1) An ideal sandwich is delicious

Failure/Error: sandwich = Sandwich.new("delicious", [])

NameError:

uninitialized constant Sandwich

# ./01-getting-started/01/spec/sandwich_spec.rb:8:in 'block (2 levels) in <top (required)>'

Finished in 0.00539 seconds (files took 0.09368 seconds to load)

1 example, 1 failure

Failed examples:

rspec ./01-getting-started/01/spec/sandwich_spec.rb:6 # An ideal sandwich is delicious

Here we can see that RSpec gives us a detailed report showing us the line of code where the error occurred, and the description of the problem, in this case sandwich has not been initialized.

With this we are following Red/Green/Refactor development practice essential to TDD and BDD. With this workflow, you’ll make sure each example catches failing or missing code before you implement the behavior you’re testing.

The next step after writing a failing spec is to make it pass.

# add to the top of the file

`Sandwich = Struct.new(:taste, :toppings)` # more about [Structs official docs](https://rubyapi.org/3.4/o/struct) and [Stackoverflow](https://stackoverflow.com/questions/25873672/ruby-class-vs-struct)

# re-run the tests

You should see now a green dot “.” and 0 failures

➜ rspec-book git:(master) ✗ bundle exec rspec 01-getting-started/01/spec/sandwich_spec.rb

.

Finished in 0.00578 seconds (files took 0.07271 seconds to load)

1 example, 0 failures

Let’s add a second spec!

Sandwich = Struct.new(:taste, :toppings)

RSpec.describe "An ideal sandwich" do

it "is delicious" do

# Developers work this way with RSpec all the time; they start with an outline and fill it in as they go

sandwich = Sandwich.new("delicious", [])

taste = sandwich.taste

expect(taste).to eq("delicious")

end

it "lets me add toppings" do

# Developers work this way with RSpec all the time; they start with an outline and fill it in as they go

sandwich = Sandwich.new("delicious", [])

sandwich.toppings << "cheese"

toppings = sandwich.toppings

expect(toppings).not_to be_empty

end

end

This example shows 2 new features, check for falsehood (using .not_to instead of .to) and check for data structure attributes

But also they are repetitive, let’s introduce 3 new RSpec features:

• RSpec hooks run automatically at specific times during testing.

• Helper methods are regular Ruby methods; you control when these run.

• RSpec’s let construct initializes data on demand.

To avoid the repetitiveness that the prior code shows, let’s start using what we described previously hooks, helper methods, let.

Hooks

The first thing that we will try in our test Suite is a before hook, which will run automatically before each example. (it reminds me to ActiveRecord callbacks)

RSpec.describe "An ideal sandwich" do

before { @sandwich = Sandwich.new("delicious", []) }

it "is delicious" do

taste = @sandwich.taste

expect(taste).to eq("delicious")

end

it "lets me add toppings" do

@sandwich.toppings << "cheese"

toppings = @sandwich.toppings

expect(toppings).not_to be_empty

end

end

The setup code is shared across specs, but the individual Sandwich instance is not. Every example gets its own sandwich. That means that you can add toppings as you do in the second spec, with the confidence that the changes won’t affect other examples.

Let’s try a different approach. (a more traditional Ruby approach)

RSpec does a lot for us; it is easy to forget that it is just playing Ruby underneath. Each example group is a ruby class, which means that we can define methods on it.

RSpec.describe "An ideal sandwich" do

def sandwich

@sandwich ||= Sandwich.new("delicious", [])

end

it "is delicious" do

taste = sandwich.taste

expect(taste).to eq("delicious")

end

it "lets me add toppings" do

sandwich.toppings << "cheese"

toppings = sandwich.toppings

expect(toppings).not_to be_empty

end

end

A typical Ruby implementation might look something like the one we just wrote which uses memoization.

This pattern is pretty easy to find in Ruby but it is not without its pitfalls. the ||= operator works by seeing if @sandwich is falsey, that is, false or nil, before creating a new @sandwich. That means that it won’t work if we are actually trying to store something falsey.

Sharing objects with let

RSpec gives us an alternative construct, let. Which handles the edge case that we previously discussed with memoization.

You can think of let as assigning a name — in this case, :sandwich — to the result of a block. This block is lazily evaluated, meaning RSpec will only run it the first time :sandwich is accessed within an example. The result is then memoized (cached) for the remainder of that example.

Our recommendation is to use these code-sharing techniques where they improve maintainability, lesson noise, and increase clarity.

RSpec.describe "An ideal sandwich" do

let (:sandwich) { Sandwich.new("delicious", []) } # [let official docs](https://rspec.info/features/3-13/rspec-core/helper-methods/let/)

it "is delicious" do

taste = sandwich.taste

expect(taste).to eq("delicious")

end

it "lets me add toppings" do

sandwich.toppings << "cheese"

toppings = sandwich.toppings

expect(toppings).not_to be_empty

end

end

At the end of the chapter there is a “Your turn” section where the author encouraged you to respond a couple of questions and for the first chapter they asked the following: Which of the three ways to reduce duplication that we have shown to you do you like the best for this example? Why? Can you think of situations where the others might be a better option?

As all good engineering questions it depends as we have seen the first one which was the before hook, it is very clean, it reads good however we saw that it has some drawbacks, like it would return nil if the instance variable is misspelled and all the refactor gymnastics that it implies for refactoring just one file even when the instance variable is not used in a group example. Then the helper method has the memoization problem and finally they let alternative covers those issues.

Some extra coding for solidifying let knowledge:

RSpec.describe "An ideal sandwich" do

let(:sandwich) { Sandwich.new("delicious", []) }

it "is delicious" do

puts "Example 1 - Sandwich object_id: #{sandwich.object_id}"

# Example 1 - Sandwich object_id: 1232

taste = sandwich.taste

expect(taste).to eq("delicious")

end

it "lets me add toppings" do

puts "Example 2 - Sandwich object_id: #{sandwich.object_id}"

# Example 2 - Sandwich object_id: 1240

sandwich.toppings << "cheese"

toppings = sandwich.toppings

expect(toppings).not_to be_empty

end

end

# within same group example

it "uses the same object within one example" do

puts "First call: #{sandwich.object_id}"

# First call: 1248

sandwich.toppings << "cheese"

puts "Second call: #{sandwich.object_id}" # Same object!

# Second call: 1248

expect(sandwich.toppings).to include("cheese") # Cheese is still there

end

A recap of Chapter 1: We explored the describe block, which is called on a group of examples, and the it block, which is called an example (or a test case in some other testing frameworks). We covered the expect keyword. We also looked at the Arrange-Act-Assert pattern. We thoroughly read through test failures and what they mean.

We understood that testing serves two purposes: documenting what the code should do, and checking that the code does what it’s supposed to do. We explored how to negate an expectation, and how to test collections such as arrays and hashes. Finally, we saw three different ways of reducing code in tests: hooks, Ruby helper methods, and the let construct.

Part I — Chapter 2. From writing specs to running them.

# Add the next file 01-getting-started/01/spec/coffee_spec.rb

class Coffee

def ingridients

@ingridients ||= []

end

def add(ingridient)

ingridients << ingridient

end

def price

1.00

end

end

RSpec.describe "A cup of coffee" do

let(:coffee) { Coffee.new }

it "costs $1" do

expect(coffee.price).to eq(1)

end

context "with milk" do

before { coffee.add :milk }

it "costs $1.25" do

expect(coffee.price).to eq(1.25)

end

end

end

And in this chapter we explore the --format documentation

➜ rspec-book git:(master) bundle exec rspec 01-getting-started/01 --format documentation

A cup of coffee

costs $1

with milk

costs $1.25 (FAILED - 1)

An ideal sandwich

is delicious

lets me add toppings

Failures:

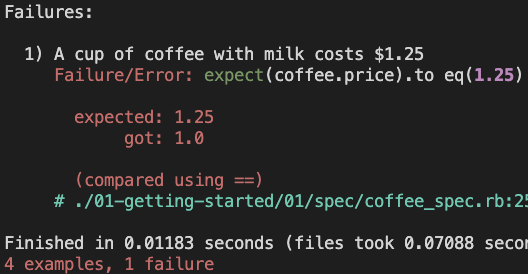

1) A cup of coffee with milk costs $1.25

Failure/Error: expect(coffee.price).to eq(1.25)

expected: 1.25

got: 1.0

(compared using ==)

# ./01-getting-started/01/spec/coffee_spec.rb:25:in 'block (3 levels) in <top (required)>'

Finished in 0.01762 seconds (files took 0.08827 seconds to load)

4 examples, 1 failure

Failed examples:

rspec ./01-getting-started/01/spec/coffee_spec.rb:24 # A cup of coffee with milk costs $1.25

Another suggestion from the book is adding the gem coderay which highlights with different colors the line that is failing. This is particularly useful when dealing with complex tests suites.

bundle exec rspec 01-getting-started/01 -fd (see the expect and 1.25)

Another tool that is shown in this chapter is how to identify a slow test by adding --profile n (n is the number of offenders we’d like to see)

# 01-getting-started/01/spec/slow_spec.rb

RSpec.describe "The sleep() method" do

it("can sleep for 0.1 seconds") { sleep 0.1 }

it("can sleep for 0.2 seconds") { sleep 0.2 }

it("can sleep for 0.3 seconds") { sleep 0.3 }

it("can sleep for 0.4 seconds") { sleep 0.4 }

it("can sleep for 0.5 seconds") { sleep 0.5 }

end

# $ bundle exec rspec 01-getting-started/01 -fd --profile 2

The sleep() method

can sleep for 0.1 seconds

can sleep for 0.2 seconds

can sleep for 0.3 seconds

can sleep for 0.4 seconds

can sleep for 0.5 seconds

Top 2 slowest examples (0.90852 seconds, 58.8% of total time):

The sleep() method can sleep for 0.5 seconds

0.50321 seconds ./01-getting-started/01/spec/slow_spec.rb:6

The sleep() method can sleep for 0.4 seconds

0.40531 seconds ./01-getting-started/01/spec/slow_spec.rb:5

Finished in 1.54 seconds (files took 0.0894 seconds to load)

5 examples, 0 failures

Also this chapter covers how to run specific tests when you don’t need to run the whole test suite (from directories, to files to even just examples).

$ rspec spec/unit/specific_spec.rb # Load just one spec file

$ rspec spec/unit spec/foo_spec.rb # Or mix and match files and directories

Example for running examples that contains word “milk” (searches are case-sensitive)

$ bundle exec rspec 01-getting-started/01 -e milk -fd

Run options: include {full_description: /milk/}

A cup of coffee

with milk

costs $1.25 (FAILED - 1)

Failures:

1) A cup of coffee with milk costs $1.25

Failure/Error: expect(coffee.price).to eq(1.25)

expected: 1.25

got: 1.0

(compared using ==)

# ./01-getting-started/01/spec/coffee_spec.rb:25:in 'block (3 levels) in <top (required)>'

Finished in 0.0128 seconds (files took 0.06799 seconds to load)

1 example, 1 failure

And if you need to run only one example or test case, you can pass rspec 01-getting-started/01/spec/coffee_spec.rb:25 and RSpec will run the example that starts on that line.

Rerunning Everything That Failed

There is one RSpec command that allows you to run just exactly the failing specs, this is pretty useful as the last command because you avoid running the whole test suite and you can fix one spec, rerun it, fix the next one and so on let’s dive in

# here we can see that same error is being brought up, example: `with milk costs $1.25`

➜ rspec-book git:(master) ✗ bundle exec rspec 01-getting-started/01/

.F.......

Failures:

1) A cup of coffee with milk costs $1.25

Failure/Error: expect(coffee.price).to eq(1.25)

expected: 1.25

got: 1.0

(compared using ==)

# ./01-getting-started/01/spec/coffee_spec.rb:29:in 'block (3 levels) in <top (required)>'

Finished in 1.55 seconds (files took 0.08332 seconds to load)

9 examples, 1 failure

Failed examples:

rspec ./01-getting-started/01/spec/coffee_spec.rb:28 # A cup of coffee with milk costs $1.25

Then we add the command --only-failures at the end and this will ask us for a path to write the last run diagnosis, in this case we added:

➜ rspec-book git:(master) ✗ bundle exec rspec 01-getting-started/01/ --only-failures

To use `--only-failures`, you must first set `config.example_status_persistence_file_path`.

# add this config line

RSpec.configure do |config|

config.example_status_persistence_file_path = 'spec/examples.txt'

end

Which will add a spec/examples.txt file with details as the following:

| example_id | status | run_time |

|---|---|---|

| ./01-getting-started/01/spec/coffee_spec.rb[1:1] | passed | 0.00064 seconds |

| ./01-getting-started/01/spec/coffee_spec.rb[1:2:1] | failed | 0.01486 seconds |

| ./01-getting-started/01/spec/sandwich_spec.rb[1:1] | passed | 0.00007 seconds |

| ./01-getting-started/01/spec/sandwich_spec.rb[1:2] | passed | 0.00163 seconds |

| ./01-getting-started/01/spec/slow_spec.rb[1:1] | passed | 0.10517 seconds |

| ./01-getting-started/01/spec/slow_spec.rb[1:2] | passed | 0.20549 seconds |

| ./01-getting-started/01/spec/slow_spec.rb[1:3] | passed | 0.30431 seconds |

| ./01-getting-started/01/spec/slow_spec.rb[1:4] | passed | 0.40278 seconds |

| ./01-getting-started/01/spec/slow_spec.rb[1:5] | passed | 0.50561 seconds |

Finally, when we re-run the --only-failures it will search for that “failed status” and run only that one! You can see it below:

➜ rspec-book git:(master) ✗ bundle exec rspec 01-getting-started/01/ --only-failures

Run options: include {last_run_status: "failed"} 👈

F

Failures:

1) A cup of coffee with milk costs $1.25

Failure/Error: expect(coffee.price).to eq(1.25)

expected: 1.25

got: 1.0

(compared using ==)

# ./01-getting-started/01/spec/coffee_spec.rb:29:in 'block (3 levels) in <top (required)>'

Finished in 0.01276 seconds (files took 0.08701 seconds to load)

1 example, 1 failure

Failed examples:

rspec ./01-getting-started/01/spec/coffee_spec.rb:28 # A cup of coffee with milk costs $1.25

The usage of command rspec –next-failure

rspec-book git:(master) ✗ bundle exec rspec 02-running-specs

# above command created spec/tea_examples.txt

example_id | status | run_time |

----------------------------------- | ------ | --------------- |

./02-running-specs/tea_spec.rb[1:1] | failed | 0.0001 seconds |

./02-running-specs/tea_spec.rb[1:2] | failed | 0.00005 seconds |

02-running-specs/tea_spec.rb

class Tea

end

RSpec.configure do |config|

config.example_status_persistence_file_path = 'spec/tea_examples.txt'

end

RSpec.describe "Tea" do

let(:tea) { Tea.new }

it "tastes like Earl Grey" do

expect(tea.flavor).to be :earl_grey

end

it "is hot" do

expect(tea.temperature).to be > 200.0

end

end

➜ rspec-book git:(master) ✗ bundle exec rspec 02-running-specs

FF

Failures:

1) Tea tastes like Earl Grey

Failure/Error: expect(tea.flavor).to be :earl_grey

NoMethodError:

undefined method 'flavor' for an instance of Tea

# ./02-running-specs/tea_spec.rb:11:in 'block (2 levels) in <top (required)>'

2) Tea is hot

Failure/Error: expect(tea.temperature).to be > 200.0

NoMethodError:

undefined method 'temperature' for an instance of Tea

# ./02-running-specs/tea_spec.rb:15:in 'block (2 levels) in <top (required)>'

Finished in 0.00362 seconds (files took 0.08398 seconds to load)

2 examples, 2 failures

Failed examples:

rspec ./02-running-specs/tea_spec.rb:10 # Tea tastes like Earl Grey

rspec ./02-running-specs/tea_spec.rb:14 # Tea is hot

Then we add the option –next-failure and it will only run the very next failure, not the whole test suite.

$ bundle exec rspec 02-running-specs --next-failure

Run options: include {last_run_status: "failed"}

F

Failures:

1) Tea tastes like Earl Grey

Failure/Error: expect(tea.flavor).to be :earl_grey

NoMethodError:

undefined method 'flavor' for an instance of Tea

# ./02-running-specs/tea_spec.rb:11:in 'block (2 levels) in <top (required)>'

Finished in 0.00049 seconds (files took 0.08649 seconds to load)

1 example, 1 failure

Failed examples:

rspec ./02-running-specs/tea_spec.rb:10 # Tea tastes like Earl Grey

This chapter focused on how specs should look and how they can be run.

It began with the introduction of the context block, which is an alias for describe. However, it has a more specific and useful purpose: it’s often used for phrases that describe a particular state or condition of the object being tested.

We learned about the command rspec --format documentation or --f d, which separates group examples from individual examples and adds indentation to visually show nesting—such as one or two levels deep.

We also explored the gem called coderay, which adds color to test output, making it easier to scan for failures. Additionally, we covered the command rspec --profile 2, which helps identify the slowest-running tests.

Next, we learned about the rspec --example word command, which allows us to run only the group examples or examples that match the given word.

Then, we explored how to run a specific test by including the line number in the command, like so:

rspec ./spec/coffee_spec.rb:25.

We also discovered a very useful command: rspec --only-failures. This runs only the tests that failed in the previous run by using a file that stores the status of each example.

We then looked into running tests in focused mode—allowing us to run only specific context, it, or describe blocks by tagging them. We can assign custom tags and then pass those tags when running rspec to filter the examples accordingly.

Another feature we explored was how to sketch out the test suite when you have more ideas in mind than time to implement them. You can use an it block with just a description (without a body), which RSpec treats as pending. You can also mark tests as incomplete using pending, skip, or xit.

Finally, we covered the --next-failure command, which runs only the next failing test from the previous run.

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

| rspec –format documentation | Displays test output with indentation to show nesting of examples. |

| rspec –profile 2 | Shows the 2 slowest-running tests to help identify performance bottlenecks. |

| rspec –example word | Runs only the examples that match the given word. |

| rspec ./spec/filename_spec.rb:25 | Runs only the test located on line 25 of the specified file. |

| rspec –only-failures | Runs only the tests that failed in the previous run. |

| rspec –next-failure | Runs the next failing test from the last run. |

Part I — Chapter 3. The RSpec Way.

All these prior features of RSpec are designed to make certain habits easy: • Writing examples that clearly spell out the expected behavior of the code • Separating common setup code from the actual test logic • Focusing on just what you need to do to make the next spec pass

Writing specs isn’t the goal of using RSpec—it’s the benefits those specs provide. Let’s talk about those benefits now; they’re not all as obvious as “specs catch bugs.”

- Specs increase confidence in your project • The “happy path” through a particular bit of code behaves the way you want it to. • A method detects and reacts to an error condition you’re anticipating. • That last feature you added didn’t break the existing ones. • You’re making measurable progress through the project.

- Eliminating fear

- With broad test coverage, developers find out early if new code is breaking existing features.

- Enabling refactoring

- Without a good set of specs, refactoring is a daunting task.

- Our challenge as developers is to structure our projects so that big changes are easy and predictable. As Kent Beck says, “for each desired change, make the change easy (warning: this may be hard), then make the easy change.”

- Guiding design

- If you write your specs before your implementation, you’ll be your own first client.

- As counterintuitive as it may sound, one of the purposes of writing specs is to cause pain—or rather, to make poorly designed code painful.

- Sustainability

- RSpec may slow initial development but ensures faster, safer future changes—unless the project is small, static, or disposable.

- Documenting behavior.

- Transforming your workflow

- Each run of your suite is an experiment you’ve designed in order to validate (or refute) a hypothesis about how the code behaves.

- You get fast, frequent feedback when something doesn’t work, and you can change course immediately

Running the entire suite Consider the difference between a test suite taking 12 seconds and one taking 10 minutes. After 1,000 runs, the former has taken 3 hours and 20 minutes. The latter has cumulatively taken nearly 7 days.

Deciding what not to test Every behavior you specify in a test is another point of coupling between your tests and your project code. That means you’ll have one more thing you’ll have to fix if you ever need to change your implementation’s behavior.

If you do need to drive a UI from automated tests, try to test in terms of your problem domain (“log in as an administrator”) rather than implementation details (“type admin@example.com into the third text field”).

Another key place to show restraint is the level of detail in your test assertions. Rather than asserting that an error message exactly matches a particular string (“Could not find user with ID 123”), consider using substrings to match just the key parts (“Could not find user”). Likewise, don’t specify the exact order of a collection unless the order is important.

Part II — Building an app with RSpec.

Part II — Chapter 4. Building an App With RSpec.

In this chapter authors decide to build an expense tracker app where users can add/search expenses.

It will use Sinatra as router and not rails since we don’t need background workers, mailers, views, asset pipelie and so on.

We need a small JSON APIs and Sinatra will do the job.

Acceptance specs => which checks the behavior of the application as a whole. By the end of the chapter, we’ll have the skeleton of a live app and a spec to test it (It makes me think like a smoke check for the core flow.)

Also, we used a “outside-in development” which means start working at outermost layer (the HTTP request/response cycle) and work your way inward to the classes and methods that contain the logic.

Create a directory and add bundler

# 04-acceptance-specs/

# add ENV['RACK_ENV'] = 'test' to spec_helper.rb

# add bundler as package manager

`bundle init`

# then in the Gemfile file add the next gems

gem "rspec", "~> 3.13"

gem "coderay" # easy-to-read, syntax-highlighted

gem 'rack-test' # provide an API for tests

gem 'sinatra' # implement the web application

# then run `bundle install` and `bundle exec rspec --init`, which will create:

`.rspec` # contains rspec command line flags

`spec/spec_helper.rb` # contains configuration options

It’s easy to feel overwhelmed as we’re deciding what to test first. Where do we start?

What’s thecore of the project? What’s the one thing we agree our API should do? It should faithfully save the expenses we record.

We’re only going to use two of the most basic features of HTTP in these examples:

• A GET request reads data from the app.

• A POST request modifies data.

First testing run 🏃

require 'rack/test'

require 'json'

module ExpenseTracker

RSpec.describe 'Expense Tracker API' do

include Rack::Test::Methods

it 'records submitted expenses' do

coffee = {

'payee' => 'Starbucks',

'amount' => 5.75,

'date' => '2025-06-10'

}

post '/expenses', JSON.generate(coffee) # This will simulate an HTTP POST request (it's a Rack::Test helper)

end

end

end

In the console we run bundle exec rspec 04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/spec/expense_tracker_api_spec.rb and we get the next error:

F

Failures:

1) Expense Tracker API records submitted expenses

Failure/Error: post '/expenses', JSON.generate(coffee)

NameError:

undefined local variable or method 'app' for #<RSpec::ExampleGroups::ExpenseTrackerAPI:0x000000011e93b538>

# ./04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/spec/expense_tracker_api_spec.rb:14:in 'block (2 levels) in <module:ExpenseTracker>'

Finished in 0.00161 seconds (files took 0.15436 seconds to load)

1 example, 1 failure

Failed examples:

rspec ./04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/spec/expense_tracker_api_spec.rb:8 # Expense Tracker API records submitted expenses

Given error tells us that we cannot use app because we have not defined it yet, so let’s add it (temporaly with a ruby helper method.)

# 04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/spec/expense_tracker_api_spec.rb

def app

ExpenseTracker::API.new

end

it 'records submitted expenses' do

...

end

# 04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/app/api.rb

require 'sinatra/base'

require 'json'

module ExpenseTracker

class API < Sinatra::Base # This class defines the barest skeleton of a Sinatra app.

end

end

Now, by adding ExpenseTracker::API and the app method we’re verifying only that the POST request completes without crashing the app.

Let’s check the response

F

Failures:

1) Expense Tracker API records submitted expenses

Failure/Error: expect(last_response.status).to eq(200)

expected: 200

got: 404

(compared using ==)

# ./04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/spec/expense_tracker_api_spec.rb:21:in 'block (2 levels) in <module:ExpenseTracker>'

Finished in 0.02102 seconds (files took 0.20637 seconds to load)

1 example, 1 failure

We need to add the route for this:

# 04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/app/api.rb

post '/expenses' do

end

Let’s fill the body of the response, we start from the testing, in this case parsing the response

# 04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/spec/expense_tracker_api_spec.rb

it 'records submitted expenses' do

coffee = {

'payee' => 'Starbucks',

'amount' => 5.75,

'date' => '2017-06-10'

}

post '/expenses', JSON.generate(coffee)

p last_response

expect(last_response.status).to eq(200)

parsed = JSON.parse(last_response.body) 👈

expect(parsed).to include('expense_id' => a_kind_of(Integer)) 👈

end

Then in our API we are going to fool the response with the following:

# 04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/app/api.rb

post '/expenses' do

JSON.generate('expense_id' => 42)

end

And as we’re inspecting the last_response we can see the @body contains the hash with key as expense_id and value as 42.

-specs/01/expense_tracker/spec/expense_tracker_api_spec.rb

#<Rack::MockResponse:0x000000011db1ba48 @original_headers={"content-type" => "text/html;charset=utf-8", "content-length" => "17", "x-xss-protection" => "1; mode=block", "x-content-type-options" => "nosniff", "x-frame-options" => "SAMEORIGIN"}, @errors="", @status=200, @headers={"content-type" => "text/html;charset=utf-8", "content-length" => "17", "x-xss-protection" => "1; mode=block", "x-content-type-options" => "nosniff", "x-frame-options" => "SAMEORIGIN"}, @writer=#<Method: Rack::MockResponse(Rack::Response::Helpers)#append(chunk) /Users/dominiclizarraga/.rbenv/versions/3.4.2/lib/ruby/gems/3.4.0/gems/rack-3.1.16/lib/rack/response.rb:359>, @block=nil, @body=["{\"expense_id\":42}"], @buffered=true, @length=17, @cookies={}>

Saving expenses is all fine and good, but it’d be nice to retrieve them. Let’s fetch expenses by date.

Let’s start by adding more expenses:

# within the example 'records submitted expenses' add these 2 hashes

it 'records submitted expenses' do

zoo = post_expense(

'payee' => 'Zoo',

'amount' => 15.25,

'date' => '2017-06-10'

)

groceries = post_expense(

'payee' => 'Whole Foods',

'amount' => 95.20,

'date' => '2017-06-11'

)

coffee = post_expense(

'payee' => 'Starbucks',

'amount' => 5.75,

'date' => '2017-06-10'

)

get '/expenses/2017-06-10'

expect(last_response.status).to eq(200)

expenses = JSON.parse(last_response.body)

expect(expenses).to contain_exactly(coffee, zoo)

end

And as you may see we added the post_expense(expense) method, so add it within describe block:

def post_expense(expense)

post '/expenses', JSON.generate(expense)

expect(last_response.status).to eq(200)

parsed = JSON.parse(last_response.body)

expect(parsed).to include('expense_id' => a_kind_of(Integer))

expense.merge('id' => parsed['expense_id'])

end

When you run the test suite bundle exec rspec 04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/spec/expense_tracker_api_spec.rb you should see an error like this:

Failures:

1) Expense Tracker API records submitted expenses

Failure/Error: expect(expenses).to contain_exactly(coffee, zoo)

expected collection contained: [{"amount" => 5.75, "date" => "2017-06-10", "id" => 42, "payee" => "Starbucks"}, {"amount" => 15.25, "date" => "2017-06-10", "id" => 42, "payee" => "Zoo"}]

actual collection contained: []

the missing elements were: [{"amount" => 5.75, "date" => "2017-06-10", "id" => 42, "payee" => "Starbucks"}, {"amount" => 15.25, "date" => "2017-06-10", "id" => 42, "payee" => "Zoo"}]

# ./04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/spec/expense_tracker_api_spec.rb:47:in 'block (2 levels) in <module:ExpenseTracker>'

Finished in 0.0305 seconds (files took 0.2402 seconds to load)

1 example, 1 failure

And the API endpoint we should enable is the following (GET '/expenses/:date')

# 04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/app/api.rb

module ExpenseTracker

class API < Sinatra::Base

post '/expenses' do

JSON.generate('expense_id' => 42)

end

get '/expenses/:date' do

JSON.generate([])

end

end

end

Now, we can mark the test_case as pending by adding right after the it block pending 'Need to persist expenses' this will change the red color from our terminal to a more friendly yellow.

And with this warning we can add a webserver gem, in this case add gem 'rackup', gem 'webrick' to Gemfile and create a file:

# 04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/config.ru # new file 🚨

require_relative 'app/api'

run ExpenseTracker::API.new

# run `cd 04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker` and from that directory [NOT rspec-book] run `bundle exec rackup`

# this will boot up a webserver

➜ expense_tracker git:(master) ✗ bundle exec rackup

[2025-07-23 14:29:17] INFO WEBrick 1.9.1

[2025-07-23 14:29:17] INFO ruby 3.4.2 (2025-02-15) [arm64-darwin24]

[2025-07-23 14:29:17] INFO WEBrick::HTTPServer#start: pid=6213 port=9292

::1 - - [23/Jul/2025:14:29:59 -0400] "GET /expenses/2017-06-10 HTTP/1.1" 200 2 0.0063

In another terminal you can try out your server with the following command:

➜ rspec-book git:(master) ✗ curl localhost:9292/expenses/2017-06-10 -w "\n"

[] # this is due to our 04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/app/api.rb GET route ✅

To recap of this chapter we began a project about tracking expenses that will register and search them, with only 2 actions. We set up bundler since we need more libraries than RSpec, such as Sinatra, SQlite, Rack, WEBrick, etc.

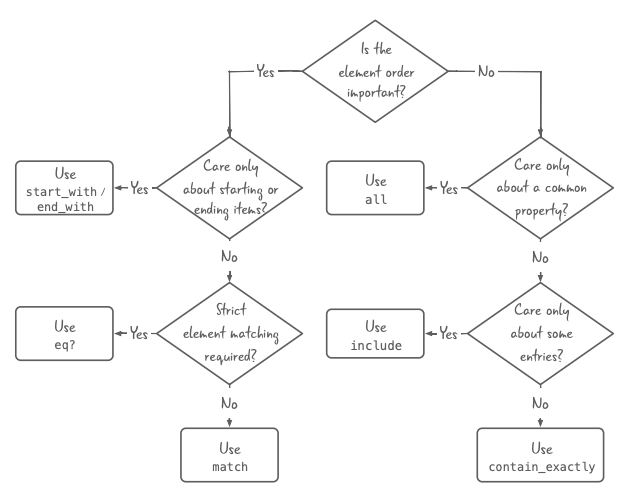

We started with an outside-in approach where we defined the outer layer of the app in this case the POST endpoint. We were encouraged to think deeply about the public API and what type of data we wanted back as a response. Then we started building the classes, and we made progress by clearing one error at a time. We used two new matchers include, a_kind_of and contain_exactly which we didn’t use but was mentioned and lastly we refactored an method for persisting a Hash of expenses and booted up the web server with bundle exec rackup. It’s important to mention that all these requests are simulated.

Part II — Chapter 5. Testing in isolation: Unit specs.

In this chapter we’re going to be picking up where we left off: the HTTP routing layer.

Unit tests typically involve isolating a class or method from the rest of the code. The result is faster tests and easier-to-find errors.

We’ll use unit spec to refer to the fastest, most isolated set of tests for a particular project.

With the unit tests in this chapter, you won’t be calling methods on the API class directly. Instead, you’ll still be simulating HTTP requests through the Rack::Test interface. Xavier Shay article about how he tests rails apps

Your tests for any particular layer—from customer-facing code down to low-level model classes—should drive that layer’s public API. You’ll find yourself making more careful decisions about what does or doesn’t go into the API.

The behavior we want to see is - what happens when an API call succeeds and when it fails.

# create a file spec/unit/app/api_spec.rb

require_relative '../app/api'

module ExpenseTracker

RSpec.describe API do

describe 'POST /expenses' do

context 'when the expense is successfully recorded' do

it 'returns the expense id'

it 'responds with a 200 (OK)'

end

context 'when the expense fails validation' do

it 'returns an error message'

it 'responds with a 422 (Unprocessable entity)'

end

end

end

end

Hit the console with bundle exec rspec 04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/app/api_spec.rb all tests should appear as “pending”.

We are still modeling the API so we want something like this:

result = @ledger.record({ 'some' => 'data' })

result.success? # => a Boolean

result.expense_id # => a number

result.error_message # => a string or nil

Remember, we’re testing the API class, not the behavior.

This is the perfect spot for test doubles. A test double is an object that stands in for another one during a test.

To create a stand-in for an instance of a particular class, you’ll use RSpec’s instance_double method, and pass it the name of the class you’re imitating. Martin Fowler’s article about test double

Add the follwoing code to file 04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/spec/unit/api_spec.rb

require_relative '../app/api'

require 'rack/test'

module ExpenseTracker

RecordResult = Struct.new(:success?, :expense_id, :error_message)

RSpec.describe API do

include Rack::Test::Methods

def app

API.new(ledger: ledger)

end

let(:ledger) { instance_double('ExpenseTracker::Ledger') }

describe 'POST /expenses' do

context 'when the expense is successfully recorded' do

it 'returns the expense id'

it 'responds with a 200 (OK)'

end

context 'when the expense fails validation' do

it 'returns an error message'

it 'responds with a 422 (Unprocessable entity)'

end

end

end

end

As with the acceptance specs, you’ll be using Rack::Test to route HTTP requests to the API class. Eventually, we’ll move the RecordResult class into the codebase.

The seam between layers is where integration bugs hide. Using a simple value object like a RecordResult or Struct between layers makes it easier to isolate code and trust your tests. Article related to catching bugs between layers.

🔦 If you feel a bit lost here is a summary of the 3 files we have written in chapter 5. 🔎

api.rb: Defines a thin HTTP API (Sinatra app). It’s the boundary/interface between the outside world and your app logic.

-

Parse incoming HTTP requests

-

Forward them to your application logic (Ledger object)

-

Return an HTTP response (JSON with status codes)

It’s like a router/controller in Rails.

api_spec.rb: Tests the API in isolation using test doubles, to control its behavior and avoid hitting the database or real logic.

This is a unit test for your API layer.

You’re using an instance_double of Ledger to isolate the API layer and check:

-

Does the API route call ledger.record?

-

Does it return the expected response if ledger.record is successful?

-

What happens if ledger.record fails?

expense_tracker_spec.rb: Acceptance-level (end-to-end) spec. It tests the whole system, using real logic (no doubles), to ensure the full behavior works.

-

It sends POST requests with expense data.

-

It sends a GET request to retrieve expenses for a given day.

-

It checks whether the correct data is returned.

-

It tests the full stack: HTTP → Sinatra → Ledger → persistence.

initialize(ledger:): Adds “dependency injection” so the API can be wired up with either real objects (in end-to-end tests) or test doubles (in unit tests).

# 04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/spec/unit/api_spec.rb

require_relative '../../app/api'

require 'rack/test'

module ExpenseTracker

RecordResult = Struct.new(:success?, :expense_id, :error_message)

RSpec.describe API do

include Rack::Test::Methods

def app

API.new(ledger: ledger)

end

let(:ledger) { instance_double('ExpenseTracker::Ledger') }

describe 'POST /expenses' do

context 'when the expense is successfully recorded' do

it 'returns the expense id' do

expense = { 'some' => 'data' }

allow(ledger).to receive(:record)

.with(expense)

.and_return(RecordResult.new(true, 417, nil))

post '/expenses', JSON.generate(expense)

parsed = JSON.parse(last_response.body)

expect(parsed).to include('expense_id' => 417)

end

it 'responds with a 200 (OK)'

end

context 'when the expense fails validation' do

it 'returns an error message'

it 'responds with a 422 (Unprocessable entity)'

end

end

end

end

The allow method configures the test double’s behavior: when the call in this case the API class invokes .record the double will return a new RecordResult instance.

Also, please notice that the expense hash doesn’t contain real data, this is ok since the whole point of the Ledger test double is that it will return a canned success or failure response.

If we run the test at this point we get the following:

Failures:

1) ExpenseTracker::API POST /expenses when the expense is successfully recorded returns the expense id

Failure/Error: expect(parsed).to include('expense_id' => 417)

expected {"expense_id" => 42} to include {"expense_id" => 417}

Diff:

@@ -1 +1 @@

-"expense_id" => 417,

+"expense_id" => 42,

# ./04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/spec/unit/api_spec.rb:27:in 'block (4 levels) in <module:ExpenseTracker>'

Top 4 slowest examples (0.03167 seconds, 91.4% of total time):

...

Let’s handle success and failure of the request in the api.rb

# 04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/app/api.rb

require 'sinatra/base'

require 'json'

require_relative 'ledger'

module ExpenseTracker

class API < Sinatra::Base

def initialize(ledger: Ledger.new)

@ledger = ledger

super()

end

post '/expenses' do

request.body.rewind

expense = JSON.parse(request.body.read)

result = @ledger.record(expense)

if result.success?

JSON.generate('expense_id' => result.expense_id)

else

status 422

JSON.generate('error' => result.error_message)

end

end

end

end

# 04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/spec/unit/api_spec.rb

require_relative '../../app/api'

require 'rack/test'

module ExpenseTracker

RSpec.describe API do

include Rack::Test::Methods

def app

API.new(ledger: ledger)

end

let(:ledger) { instance_double('ExpenseTracker::Ledger') }

describe 'POST /expenses' do

context 'when the expense is successfully recorded' do

let(:expense) { { 'some' => 'data' } }

before do

allow(ledger).to receive(:record)

.with(expense)

.and_return(RecordResult.new(true, 417, nil))

end

it 'returns the expense id' do

post '/expenses', JSON.generate(expense)

parsed = JSON.parse(last_response.body)

expect(parsed).to include('expense_id' => 417)

end

it 'responds with a 200 (OK)' do

post '/expenses', JSON.generate(expense)

expect(last_response.status).to eq(200)

end

end

context 'when the expense fails validation' do

let(:expense) { { 'some' => 'data' } }

before do

allow(ledger).to receive(:record)

.with(expense)

.and_return(RecordResult.new(false, 417, "Expense incomplete"))

end

it 'returns an error message' do

post '/expenses', JSON.generate(expense)

parsed = JSON.parse(last_response.body)

expect(parsed).to include('error' => 'Expense incomplete')

end

it 'responds with a 422 (Unprocessable entity)' do

post '/expenses', JSON.generate(expense)

expect(last_response.status).to eq(422)

end

end

end

end

end

The last excersice is to add GET /expenses/:date starting from writing down tests:

- Write the

describeblock, then thecontext, theitblocks. - The

API::Sinatrais already working (we have not defined the storage engine yet) - Add

instance_doubleofledger(RecordResultis no longer needed) - Add the method

expenses_on(date)on theLedgerclass. - Generate a sample data of the JSON we want as return. (The hash should contain amount, date and payee)

- Modify the

api.rbsince theGETroute always return empty array. It shoudl handle success and failure too.

Here is the api.rb and the api_spec.rb. These refactored specs report “just the facts” of the expected behavior.

# 04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/app/api.rb

get '/expenses/:date' do

date = params[:date]

unless /\A\d{4}-\d{2}-\d{2}\z/.match?(date)

status 400

return JSON.generate({ error: "Invalid date format" })

end

expenses = @ledger.expenses_on(date)

if expenses.any?

JSON.generate(expenses)

else

JSON.generate([])

end

end

# 04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/spec/unit/api_spec.rb

module ExpenseTracker

RSpec.describe API do

include Rack::Test::Methods

def app

API.new(ledger: ledger)

end

let(:ledger) { instance_double('ExpenseTracker::Ledger') }

describe "GET /expenses/:date" do

context "when expenses exist on given date" do

let(:expense_canned_response) { [ {"amount" => 5.50, "date" => '2017-06-10', "payee" => "Starbucks"} ] }

before do

allow(ledger).to receive(:expenses_on)

.with('2017-06-10')

.and_return(expense_canned_response)

end

it "returns the expense records as JSON" do

get '/expenses/2017-06-10'

parsed = JSON.parse(last_response.body)

expect(parsed).to eq(expense_canned_response)

end

it "responds with a 200 (OK)" do

get '/expenses/2017-06-10'

expect(last_response.status).to eq(200)

end

end

context "when expenses don't exist on given date" do

let(:expense_not_found) { [] }

before do

allow(ledger).to receive(:expenses_on)

.with('2017-05-12')

.and_return(expense_not_found)

end

it "returns an empty array as JSON" do

get '/expenses/2017-05-12'

parsed = JSON.parse(last_response.body)

expect(parsed).to eq(expense_not_found)

end

it "responds with a 200 (OK)" do

get '/expenses/2017-05-12'

expect(last_response.status).to eq(200)

end

end

context "when the date format is not valid" do

it "returns a 400 Bad Request" do

get '/expenses/2012,12,12'

expect(last_response.status).to eq(400)

end

it "returns an error message" do

get '/expenses/2012,12,12'

expect(JSON.parse(last_response.body)).to eq({ "error" => "Invalid date format" })

end

end

end

end

end

I’ll add more routes and test cases so that I can practice more

- GET /expenses – List all expenses (not just by date)

- GET /expense/:id ————- These should added once we setup SQlite ————-

- DELETE /expenses/:id – Delete a specific expense

- PUT /expenses/:id – Update an existing expense

- GET /expenses/stats/:month – Show monthly summary

- POST /budgets – Set a budget limit for a category or month

- GET /categories

- GET /expenses?category=Food&date=2025-07-10 (this one needs

query params, we’re currently usingroute params)

In this chapter, we explored how to move from acceptance tests — which ensure that the entire application works as a whole — to unit tests, which isolate specific parts of the code, such as routing logic.

Unit tests typically run without a live server or real database, and instead focus on one class or method at a time. The benefits of this approach are faster test execution and clearer identification of where errors occur.

Rather than calling methods directly on the API class, we simulated HTTP requests using the Rack::Test interface. This aligns with the common testing principle of exercising a class through its public interface, which leads to better design decisions and a more user-focused API.

We also examined the Ledger class and introduced dependency injection (DI). In Ruby, this is as simple as passing an object as an argument to the constructor, like so:

initialize(ledger: Ledger.new)

This technique makes it easier to swap in test doubles when testing, allowing us to isolate the API class from the actual persistence layer.

A test double is a generic term for objects that stand in for real ones during testing. Depending on the testing framework, they might be called mocks, stubs, fakes, or spies. In RSpec, we use the term double. Our goal was to create a fake Ledger object to test only the API logic — without involving real data storage — making the tests faster and more focused. instance_double(class_to_fake)

We also encountered verifying doubles, a powerful RSpec feature that ensures your test doubles reflect the real object’s interface. This helps avoid fragile tests. In our case, forgetting to instantiate the Ledger correctly caused RSpec to raise an error — a valuable signal that our double wasn’t matching the actual interface.

If you ever need to inspect a full error stack trace during testing, you can run RSpec with the --backtrace or -b flag:

bundle exec rspec -b

Part II — Chapter 6. Getting real. Integration specs.

Now we have a solid HTTP routing layer designed with the help of unit specs. These specs assummed that the underlying dependencies would eventually be implemented.

Now, it’s time to write those dependecies for real.

Add the sequel and sqlite gems:

bundle add sequel sqlite3

Remember we need to have 3 differents databases for testing, development and production so that we dont clobber with real data.

Then add the 3 files (2 for configurations and 1 for the expenses migration)

# 04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/config/sequel.rb

require 'sequel'

DB = Sequel.sqlite("./db/#{ENV.fetch('RACK_ENV', 'development')}.db")

# 04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/spec/support/db.rb

# suite-level hook.

# The following code will make sure the database structure is set up and empty,

# ready for your specs to add data to it

RSpec.configure do |c|

c.before(:suite) do

Sequel.extension :migration

Sequel::Migrator.run(DB, 'db/migrations')

DB[:expenses].truncate

end

end

# 04-acceptance-specs/01/expense_tracker/db/migrations/0001_create_expenses.rb

Sequel.migration do

change do

create_table :expenses do

primary_key :id

String :payee

Float :amount

Date :date

end

end

end

Regarding the before(:suite) hook A typical hook will run before each example. This one will run just once: after all the specs have been loaded, but before the first one actually runs. That’s what before(:suite) hooks are for.

Then run the migration with bundle exec sequel -m ./db/migrations sqlite://db/development.db --echo

Outout you may see:

2025-08-05 13:32:31 INFO: (0.001937s) PRAGMA foreign_keys = 1

2025-08-05 13:32:31 INFO: (0.000010s) PRAGMA case_sensitive_like = 1

2025-08-05 13:32:31 INFO: (0.001011s) SELECT sqlite_version()

2025-08-05 13:32:31 INFO: (0.000890s) CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS `schema_info` (`version` integer DEFAULT (0) NOT NULL)

2025-08-05 13:32:31 INFO: (0.000039s) SELECT * FROM `schema_info` LIMIT 0

2025-08-05 13:32:31 INFO: (0.000029s) SELECT 1 AS 'one' FROM `schema_info` LIMIT 1

2025-08-05 13:32:31 INFO: (0.000415s) INSERT INTO `schema_info` (`version`) VALUES (0)

2025-08-05 13:32:31 INFO: (0.000050s) SELECT count(*) AS 'count' FROM `schema_info` LIMIT 1

2025-08-05 13:32:31 INFO: (0.000028s) SELECT `version` FROM `schema_info` LIMIT 1

2025-08-05 13:32:31 INFO: Begin applying migration version 1, direction: up

2025-08-05 13:32:31 INFO: (0.000512s) CREATE TABLE `expenses` (`id` integer NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT, `payee` varchar(255), `amount` double precision, `date` date)

2025-08-05 13:32:31 INFO: (0.000423s) UPDATE `schema_info` SET `version` = 1

2025-08-05 13:32:31 INFO: Finished applying migration version 1, direction: up, took 0.001072 seconds

Then we had to create a spec/ledger_spec.rb which will test out the Ledger class behavior.

require_relative '../../../app/ledger'

require_relative '../../../config/sequel'

require_relative '../../support/db'

module ExpenseTracker

RSpec.describe Ledger, :aggregate_failures do

let(:ledger) { Ledger.new }

let(:expense) do

{

'payee' => 'Starbucks',

'amount' => 5.75,

'date' => '2017-06-10'

}

end

describe '#record' do

context "with a valid expense" do

it "succesfully saves the expense in the DB" do

result = ledger.record(expense)

expect(result).to be_success

expect(DB[:expenses].all).to match [a_hash_including(

id: result.expense_id,

payee: 'Starbucks',

amount: 5.75,

date: Date.iso8601('2017-06-10')

)]

end

end

end

end

end

And don’t forget to add the logic into the Ledger class

def record(expense)

DB[:expenses].insert(expense)

id = DB[:expenses].max(:id)

RecordResult.new(true, id, nil)

end

Here we just leveraged 2 new matchers be_success and match [a_hash_including] This particular example we detoured a bit from TDD since we declared 2 expects under the same it block but we did it judiciously since every test that touches the DB is slower so if we follow rigorously one expect per test case we’re going to be repeating that setup and teardown many times.

Also, we did added the metada :aggregate_failures so that RSpec doesn’t abort execution at the first error but to run all tests even with failures!

With this out of the way, let’s add a test for invalid records

it "rejects the expense as invalid" do

expense.delete('payee')

result = ledger.record(expense)

expect(result).not_to be_success

expect(result.expense_id).to eq(nil)

expect(result.error_message).to include('`payee` is required')

expect(DB[:expenses].count).to eq(0)

end

This will break our test, but that’s all the purpose of the red-green-refactor cycle. Now let’s add the valdiation for Ledger class

class Ledger

def record(expense)

unless expense['payee']

return RecordResult.new(false, nil, '`payee` is required')

end

DB[:expenses].insert(expense)

id = DB[:expenses].max(:id)

RecordResult.new(true, id, nil)

end

end

Something important that authors mention is that everytime we run the test suite we are adding records to our db which is not good practice, therefore they suggest to add the next RSpec configuration for leeting RSpec that everytime it finds :db tag, it should perform a DB transaction which will entails seting up the DB before running the tests and wiping out after the test suite is ran.

# suppor/db.rb

c.around(:example, :db) do |example|

DB.transaction(rollback: :always) { example.run }

end

Here is a detailed list of steps that this script will do:

- RSpec calls our

around hook, passing it the example we’re running. - Inside the hook, we tell Sequel to start a new database transaction.

- Sequel calls the inner block, in which we tell RSpec to run the example.

- The body of the example finishes running.

- Sequel rolls back the transaction, wiping out any changes we made to the database.

- The around hook finishes, and RSpec moves on to the next example.

Now let’s jump to implement the GET /expenses_on(:date) endpoint. First start with the test

describe "#expenses_on" do

it "returns all expenses for the date provided" do

result_1 = ledger.record(expense.merge('date' => '2017-06-10'))

result_2 = ledger.record(expense.merge('date' => '2017-06-10'))

result_3 = ledger.record(expense.merge('date' => '2017-06-11'))

expect(ledger.expenses_on('2017-06-10')).to contain_exactly(

a_hash_including(id: result_1.expense_id),

a_hash_including(id: result_2.expense_id)

)

end

it "returns an empty array when there are no matching expenses" do

expect(ledger.expenses_on('2017-06-10')). to eq([])

end

end

# then the ruby logic

def expenses_on(date)

DB[:expenses].where(date: date).all

end

This should pass all good!

Conclusion: while searching some other RSpec keywords i found this useful RSpec cheat sheet from Thoughtbot also we used the :aggregate_failures feature twice. This option allows the RSpec to continue running the entire test suite even when a test fails. We first applied it at the individual test case level, and then moved it up to an example group, which signaled RSpec to apply that behavior to the entire group.

We also introduced two new matchers: be_success and match a_hash_including.

Another key point we learned is that every spec interacting with the database will run more slowly. Because of this, we need to be judicious when applying the TDD methodology, which encourages writing one expect per test case. In some situations, we combined multiple expect statements within the same test case to speed up execution.

Finally, we explored the --bisect command, which is useful for identifying order-dependent tests. An order dependency occurs when a test fails only if another specific test runs before it. The --bisect command automatically isolates the minimal set of examples that cause the failure by repeatedly running subsets of your tests.

Example:

# First, run with a specific seed to reproduce the failure

rspec --seed 12345

# If you see a failure, run:

rspec --seed 12345 --bisect

Sample output:

Bisect started using options: "--seed 12345"

Reducing test suite by half...

...

The minimal reproduction command is:

rspec ./spec/foo_spec.rb[1:3] ./spec/bar_spec.rb[1:5] --seed 12345

This tells you exactly which tests together trigger the failure, so you can debug the cause. It’s essentially automated detective work for the classic “this test only fails when that other one runs first” problem.

Part III — RSpec Core.

Part III — Chapter 7. Structuring code examples.

we’ve gained the mental model of “where things go” (either files or groups or examples or setup!)

we’ve have written short, clear examples that explain exactly what the expected behavior of the code is laid examples into logical groups, not oly to share setup but foor keep related specs together

you’ll learn how to organize specs into groups, you’ll know where to put shared setup code and the trade-offs.

This will make the tests easier to read and maintain.

well-structures specs are about more than tidiness, sometimes you attach special behavior to certain examples or groups, like setting up a database or adding a custom error handling. the mechanism of metada (:tags) relies on good grouping.

Getting the words right.

Every RSpec is the example group in other testing Frameworks it is called test case class and it has multiple purposes:

- gives a logical structure for understanding how individual examples relate to one another

- describes the context such as a particular class, method or situation of what you are testing,

- provides a ruby class to act as a scope for your shared logic, such as hooks let definition and helper methods,

- runs, set up and tear down code shared by several examples.

The basic includes group examples, examples and expectations.

describe creates an example group. This is the place where you put what you say you are testing, the description can be either a string a ruby class, a module or an object. when you use a class it has some advantages because it requires the class to exist and to be spelled correctly, Also you place here the tag filtering with extra information and that tag will be applied to the nested examples

it creates a single example, you pass a description of the behavior you are specifying as with describe you can also pass custom metadata to make it more specific remember that for bdd the crucial part is to “getting the words right”.

Now, so much alternatives for describe that makes more sense when the examples within that group all relate to a single class method or module that alternative is context which will make it more readable and considering that this is for the long term maintainability, and it will show the intent behind the code.

another alternative is example instead of the it and it may be used when you are providing several data examples rather than several sentence about the subject or describing a behavior it will read much more clearly and lastly we have the specified instead of the it

RSpec also provides the flexibility for adding the names you want in the book shows how you can combine this gem with binding.pry and how you can add an alias to the spec_helper.rb file and use that in your Cascade or example and that will add the pry: trueto metadata to its respective example group or single example and with this you can quickly toggle the pry behavior on and off just by adding or removing the name you define in the spec_helper.rb.

Sharing logic.

the main three organization tools are let definitions, hooks, and helper methods below is a code snippet that contains all of the three

RSpec.describe 'POST a successful expense' do

# let definitions

let(:ledger) { instance_double('ExpenseTracker::Ledger') }

let(:expense) { { 'some' => 'data' } }

# hook

before do

allow(ledger).to receive(:record)

.with(expense)

.and_return(RecordResult.new(true, 417, nil))

end

# helper method

def parsed_last_response

JSON.parse(last_response.body)

end

end

We have used the let definition several times in this book they are great for setting up anything that can be initialized in a line or two of code, and they give you the lazy evaluation for free which means that they are not going to be run until you actually invoke them.

then we have the hooks that are for situations where they let definition block just won’t cut it. the important thing about hooks is the one and how often you want the hook to run.

Hooks.

“writing a hook involves two concepts. the type of hook controls when it runs relative to your examples. the scope controls how often your hook runs.”

For the when the hook should run we have three different types before, after, and around. as the name implies, you’re before hook will run before your examples. after hooks guarantee to run after your examples, even if the example fails or did before hook races an example. this hooks are intended to clean up after your setup logic and specs. this style of hook is easy to read, but it does split the setup and tear down logic into two halves that we have to keep track of.

When your database cleanup logic doesn’t fit neatly into a transactional around HOOK, we recommend using a before hook for the following reasons: if you forget to add the before hook to a particular spec the failure will happen in that example rather than a later one. when you run a single example to diagnose a failure the records will stick around in the database so that you can investigate them.

the around hook it’s a bit more complex because they sandwich your spec code inside your hook, so part of the hook runs before the example and part runs after. the behavior of these two Snippets is the same; it is just a question of which reads better for your application.

RSpec.describe MyApp::Configuration do

around(:example) do |ex|

original_env = ENV.to_hash

ex.run

ENV.replace(original_env)

end

end

Then we have the config hooks and this is if you need to run your hooks for multiple groups. you can define the hooks once for your entire Suite in the configuration typically spec _ helper.rband they’ll run for every example in your test suite

RSpec.configure do |config|

config.around(:example) do |ex|

original_env = ENV.to_hash

ex.run

ENV.replace(original_env)

end

end

and with this they will run for every example in your test suite note the trade-off here:

- Global hooks reduced duplication but can lead to surprising action at a distance effect in your aspects.

- hooks inside example groups are easier to follow but it is easy to leave out an important Hook by mistake when you are creating a new spec file.

we do recommend only use config hooks for things that are not essential for understanding how your specs work. the Beats of logic that isolate each example, such as a database transaction or environment sandboxing, or prime candidates.

we prefer to keep things simple and run our hooks unconditionally. if, however, our config hooks are only needed by a subset of examples on particularly if they are as low, we will use metadata to make sure they run only for the subset that need them.

now that we have seen when to run the hooks either before or after or around let’s see the scope.

this is meant when I hook needs to do a really timing tensive operation like creating a bunch of database tables or launching a live web server running the hook once per second will be cost provided. for this cases you can run the hook just once for the entire Suite of specs or once per example group. hooks take a symbol like :suite or :context argument to modify this code.

RSpec.describe 'Web interface to my thermostat' do

before(:context) do

WebBrowser.launch

end

after(:context) do

WebBrowser.shutdown

end

end

we only consider using context hook scope for side effects such as launching a web browser, that’s satisfy both of the following two conditions:

does not interact with things that have a per example life cycle is noticeable slow to run

when you use a context hook scope your responsible for cleaning up any resulting state otherwise, it can cause other specs to pass or fail incorrectly

this is particularly common problem with database code. any records created in a before context hook scope will not run in your per example database transactions. the records will stick around after the example groups

If you need to run a piece of setup call just once, before the first example begins that’s what :suite

There may be some old syntax that you may find in code bases which is Old new before(:each) became before(:example) before(:all) became before(:suite)

Something important when a example group is nested the before hooks run from the outside in and the after hooks run from the inside out.

when to use hooks we have seen that hooks serve two different purposes:

removing duplicate it or incidental details that will distract readers from the point of your example.

expressing the English descriptions of your example groups as executable code

Abusing RSpec hooks will make you skip all over your spec directory to trace program flow.

Helper methods.

Sometimes, we can get too clever for our own good and misuse these constructs in an effort to remove every last bit of repetition from our specs. Let’s see an example

RSpec.describe BerlinTransitTicket do

let(:ticket) { BerlinTransitTicket.new }

before do

# These values depend on `let` definitions

# defined in the nested contexts below!

#

ticket.starting_station = starting_station

ticket.ending_station = ending_station

end

let(:fare) { ticket.fare }

context 'when starting in zone A' do

let(:starting_station) { 'Bundestag' }

context 'and ending in zone B' do

let(:ending_station) { 'Leopoldplatz' }

it 'costs €2.70' do

expect(fare).to eq 2.7

end

end

context 'and ending in zone C' do

let(:ending_station) { 'Birkenwerder' }

it 'costs €3.30' do

expect(fare).to eq 3.3

end

end

end

With all these jumps around we have welcomed a behavior defined by the TDD community calls this separation of cause and effect a mystery guest link, now let’s see how would be with a smart usage of helper methods

RSpec.describe BerlinTransitTicket do

def fare_for(starting_station, ending_station)

ticket = BerlinTransitTicket.new

ticket.starting_station = starting_station

ticket.ending_station = ending_station

ticket.fare

end

context 'when starting in zone A and ending in zone B' do

it 'costs €2.70' do

expect(fare_for('Bundestag', 'Leopoldplatz')).to eq 2.7

end

end

context 'when starting in zone A and ending in zone C' do

it 'costs €3.30' do

expect(fare_for('Bundestag', 'Birkenwerder')).to eq 3.3

end

end

end

Now, it’s explicit exactly what behavior we’re testing, without our needing to repeat the details of the ticketing API. (these helper methods can be extracted into modules and be glued together by calling include into the group example)

Sharing examples groups

As we have seen, plain old Ruby modules work really nicely for sharing helper methods across example Scripts. but that’s all they can share. if you want to reuse an example, a let construct or a hook, you will need to reach for another two; shared example groups.

RSpec provides multiple ways to create and use shared sample grips. This come in pairs, with one method for defining a share group and another for using it:

- shared_context and include_context are for reusing common setup and helper logic..